I had a short chat with The Project about it yesterday; the logistics didn't work out for a longer chat as I was out to Christchurch to help launch an excellent new book on smart water markets - more on that another time. I'd put together a few notes in case I was to have had a longer chat; I'll share those here.

The bulk of Morgan's proposal would be funded by cancelling National's tax package, with minor bits coming from forecast future surpluses ($400m), canning student allowances and student loan living costs for folks in that age cohort (maybe $267m they think), and job-seeker support for those in that age cohort.

I don't know how this interacts with WFF and consequent fiscal effect. Some of the benefit could be clawed back - with potentially lower fiscal cost.

The bulk of the cost comes from cancelling National’s tax package. That package pushed out the income tax thresholds for the two lower tax boundaries. So providing funds to those 18-23 is at the expense of reduced taxes for every other cohort.

National’s tax package bumped up the accommodation benefit for students and hiked the accommodation supplement. In current rental markets, that programme would mostly subsidise landlords rather than help tenants; just giving that money as cash transfer to 18-23 year olds may not be all that bad.

More generally, there are two basic ways of trying to provide income support. Targeted programmes, like those that the government currently runs, and like those it will be further developing as part of the investment approach, seek to direct funds to particular sorts of need. They get messy and complicated very quickly as necessary part of targeting, and the rules can often feel perverse. If you want to make sure that kids in households with the least support get the most help, you need checks around what kinds of support are available in the household – and that’s where all of the monitoring stuff around live-in partners and the like comes in.

These programmes are able to deliver targeted benefits at tolerable cost, focused most closely on areas of greatest identified need. And the Investment Approach will ramp all of that up to direct funds to programmes that do the most good in improving lives, as measured by reduced reliance on benefits. Note that the object there isn’t the reduced reliance on benefits but that it’s a signal of other things having gone wrong.

A UBI is at the opposite end of the scale. It provides blanket payments to everybody regardless of need. The UBI forgoes targeting in favour of simplicity, but at the expense of high cost. So while a UBI would reduce the high EMTRs facing a lot of people on multiple benefits who are working 20-30 hours per week, where combined clawback rates can mean that workers only keep 10 cents or less from each dollar earned (in some cases), it is at the expense of higher EMTRs for all other earners. And then the net effect depends on whether you do more good by reducing large perverse incentives for a small group of people, or by avoiding (relatively) smaller perverse incentives for a much larger group of people.

TOP is right to point to the unfairness of some of the support provided to students that is not provided to others starting out in the workforce. They propose taking away some of the extra support provided to tertiary students (though fall short of re-introducing interest on student loans, which they should have), but apply the savings to a blanket payment to everyone aged 18-23 regardless of need.

And where they've maintained benefit payments above $10k for those currently in receipt of benefit packages over $10k, they've also maintained some of the costly hoop-jumping (and high EMTRs) that are part of the costs of the current system.

As for incentive effects and work, here's a recent evaluation of what happened in Manitoba's Mincome experiment.

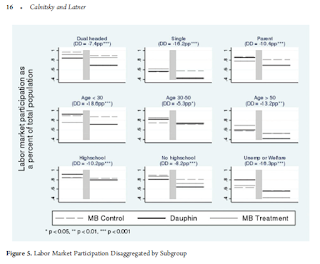

Thus, Figure 5 graphs overall trajectories in order to get a general picture of subgroup trends. Subgroups are displayed as baseline and study period averages for ease of presentation, and treatment effects are shown in parentheses in Figure 5. Among the most consequential, Mincome’s average treatment effect (the difference between changes in Dauphin and changes in the Manitoba control) for singles is a 16.2 percentage point fall in household participation in the labor market. Among young people there is a similarly large treatment effect, at 18.6 percentage points. Dual-headed households appear less sensitive to Mincome. For this group, the equivalent treatment effect is 7.4 percentage points. Thus, the overall experimental effect on labor market participation is disproportionately driven by changes in young and single-headed households.

So the biggest drop in labour market participation was among youths.

Dauphin's guaranteed family income started at $19,500: about half of annual household income at the time. Morgan's proposed $10,000 is much lower than that relative to median household income in New Zealand, so corresponding effects on labour market participation would be expected to be lower than those found in Manitoba.

While the authors note that drops in participation would not be large enough to cause problems in overall scheme financing, note that Mincome wasn't self-financing. Lots of people in Dauphin weren't in the experiment, and the money for the experiment came from overall government revenues.

That makes it harder to tell what the real effect on participation would be. On the one hand, you might expect people who wanted to be able to drop out of the labour force would be disproportionately willing to participate in the experiment, which would mean the found effect is larger than you might expect for the population overall. On the other hand, you might expect that if everyone faced the kinds of tax rates necessary to fund a UBI scheme, dropping out of work for current workers would look more attractive. In that case, you'd expect real-world effects to be larger than those found in Mincome for payments comparable to those used in Mincome.

No comments:

Post a Comment