A tallying of the costs of road accidents that included fatalities but ignored disabilities would result in too little investment in road improvements that might reduce accident rates.

Tallying Covid's morbidity costs is an awful lot harder than tallying the morbidity costs of road accidents. We have years of data on road accidents and anything in New Zealand that comes consequent to a road accident runs through our ACC system - it's then not all that hard to get a handle on costs.

Covid is a lot harder. We all hear horror stories about the ongoing consequences for some who catch it. If those stories represent one in a million cases, they wouldn't have much effect on policy decisions. If they represent one in ten cases, then they're a big deal. But it is darned hard to find anything that summarises the numbers.

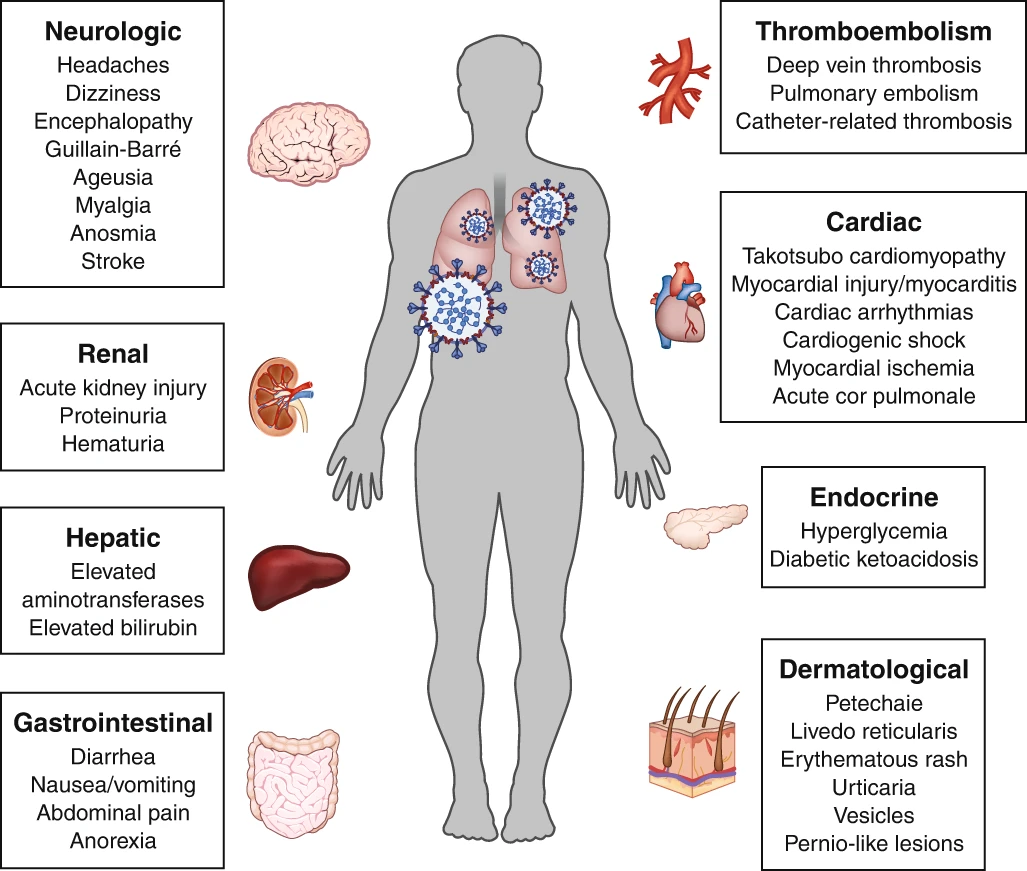

Dr Jin Russell points to an article published in Nature back in July that summarises the various conditions that can be consequent to Covid.

Here's the abstract:

Although COVID-19 is most well known for causing substantial respiratory pathology, it can also result in several extrapulmonary manifestations. These conditions include thrombotic complications, myocardial dysfunction and arrhythmia, acute coronary syndromes, acute kidney injury, gastrointestinal symptoms, hepatocellular injury, hyperglycemia and ketosis, neurologic illnesses, ocular symptoms, and dermatologic complications. Given that ACE2, the entry receptor for the causative coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, is expressed in multiple extrapulmonary tissues, direct viral tissue damage is a plausible mechanism of injury. In addition, endothelial damage and thromboinflammation, dysregulation of immune responses, and maladaptation of ACE2-related pathways might all contribute to these extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Here we review the extrapulmonary organ-specific pathophysiology, presentations and management considerations for patients with COVID-19 to aid clinicians and scientists in recognizing and monitoring the spectrum of manifestations, and in developing research priorities and therapeutic strategies for all organ systems involved.

The piece is written for clinicians, telling them things potentially to watch for. Turning it into something that could be used in cost-benefit assessment would be a pretty big job.

There are rather a few potential consequences.

The article will note things like "in a cohort of 107 patients admitted to a single-center ICU with COVID-19, their rates of pulmonary emboli were notably higher than those of patients admitted to the same ICU during the same interval in 2019 (20.6% versus 6.1%, respectively)."

But using things like that in any CBA work would require knowing what proportion of COVID cases in that area wind up in ICU. You need to know what proportion of infections wind up with that outcome to be able to say anything . You can make simplifying assumptions about the proportion of cases that wind up in ICU.

Other conditions are reported as fractions of hospitalised patients: 17% of hospitalised patients in Wuhan wound up with cardiac arrhythmias. But what fraction of infections wound up in hospital? And were those conditions presenting only while in hospital during infection, or did they persist? Acute kidney injuries occurred in 37% of patients hospitalised in New York, with 14% requiring dialysis. But again, what fraction wind up in hospital, and is this something from which people recover, or does it continue?

I really wish we had a better picture of the state of play.

There are a bit over 1500 people in New Zealand who have recovered from Covid. They would not be representative of the population overall, should New Zealand ever have a broader infection. Those here who have recovered are going to reflect the cases we have had: mostly those who have returned from overseas, who are younger and healthier.

But despite that, surely it would be worth knowing the outcomes for that cohort. It would be cheap in the grand scheme of things. The government could pay GPs for a series of follow-up visits with those who have recovered, and pay those who have recovered for their time. It feels like it would be hard to spend $10 million on this. $5k split between GP and patient would only get you to $7.5m.

The series of follow-up visits would check for any ongoing health effects of Covid. I'd also really like to get some measures on just how bad the whole experience was for those who have had it. I'm not a big fan of numbers expressed in survey values as compared to revealed preference, but I'd expect we'd learn something useful out of it here.

Get the big table of conditions that have existing DALY or QALY figures attached to them. Ask each recovered patient "So, which would be worse? Getting Covid again exactly as you had it, but with no longer term consequences, or breaking your femur?" Running that over a series of conditions would get a distribution of valuations, among the cohort here who have recovered from it. You'd have to be rather careful in extrapolating that up to the population, because that cohort will have far fewer pre-existing conditions that worsen things. But at least it would be something of a start.

I don't get why this kind of follow-up work isn't being done. Somebody would have to fund it, and it would likely be more expensive than a standard grant. Could it just be that nobody thought to put in a funding line for this kind of thing?

No comments:

Post a Comment