- Australian water rats have figured out that the hearts and livers of poisonous cane toads are fine to eat. I would love to know how rats figured this out, and how the practice spread.

- Australia's poisonous legislators have passed a piece of anti-terrorism legislation every 6.7 weeks since September 11, 2001. The water rats may not help in getting rid of this nuisance.

- A perhaps-unintended consequence of anti-Uber activism in California making it harder for people to work as contractors: dancers at strip clubs become employees when many didn't want to.

- Merivale NIMBYs.

- Another for the "I guess we just can't have nice things" file. The Police Minister wants to allow pill testing at events; it's an excellent harm-reduction strategy. New Zealand First has blocked it, reckoning it would increase drug use. And while I'd be pretty confident that Labour and the Greens could find enough supporters for pill-testing in the National/ACT caucuses than would be needed to get it over the line, the usual politics stuff means we can't have nice things.

Monday, 30 September 2019

Afternoon roundup

The worthies on the closing of the browser tabs:

Labels:

assorted links,

australia,

drugs,

labour law,

terrorism

Policy bets

I'm a big fan of betting, but rules that stop players and coaches from betting make sense. You don't want somebody to throw the game to make sure that their bet goes the way they'd hoped.

Bernard Hickey's morning roundup includes the following bit of news:

I'd bet substantially against bans on internal combustion engines, but I'd bet in favour of wider use of carbon pricing - if the government hadn't banned iPredict. I'd count the increase in nuclear capacity as wishful thinking - I wish it would happen, but there are a lot of layers of stupid to cut through to get there. And I expect that private-sector funds who've signed up to the Principles will take the report's predictions with a bit of scepticism.

But here's the part that worries me:

Bernard Hickey's morning roundup includes the following bit of news:

Prepare for policy shock - The UN-supported Principles for Responsible Investment group, which has nearly 500 fund managers looking after nearly US$90 trillion in assets, warned last week that financial markets had not priced-in the likely near-term policy response to climate change. It issued a report on a new project called ‘The Inevitable Policy Response,’ which sees a political and financial tipping point by 2025 that forces dramatic political action. That would include “bans on coal, and on internal combustion engines; an increase in nuclear capacity and bioenergy crops; greater effort on energy efficiency and re/afforestation; wider use of carbon pricing and increasing the supply of low-cost capital to green economy projects.”And this is all fair enough. Lots of investment decisions depend on assessments of policy risk. The big funds will have all kinds of folks watching over those policy risks to try to make sure they're appropriately positioned.

“Government action to tackle climate change has so far been highly insufficient to achieve the commitments made under the Paris Agreement, and the market’s default assumption appears to be that no further climate-related policies are coming in the near-term. Yet as the realities of climate change become increasingly apparent, it is inevitable that governments will be forced to act more decisively than they have so far,” the report’s authors PRI, Vivid Economics and Energy Transition Advisors write.

“The question for investors now is not if governments will act, but when they will do so, what policies they will use and where the impact will be felt. The IPR project forecasts a response by 2025 that will be forceful, abrupt, and disorderly because of the delay.”

I'd bet substantially against bans on internal combustion engines, but I'd bet in favour of wider use of carbon pricing - if the government hadn't banned iPredict. I'd count the increase in nuclear capacity as wishful thinking - I wish it would happen, but there are a lot of layers of stupid to cut through to get there. And I expect that private-sector funds who've signed up to the Principles will take the report's predictions with a bit of scepticism.

But here's the part that worries me:

The NZ Super Fund is a founding signatory and the project is due to start publishing detailed modeling from late September on the effects of this shift on the macro-economy and asset values.

If the sovereign wealth funds start making plays predicated on their assessment that governments will ban internal combustion engines by 2025 (etc), and if governments do not want their sovereign wealth funds to realise substantial losses, does that start affecting policy.

Do we want rugby referees betting on the game they're officiating?

Previously: State-owned investment vehicles.

Friday, 27 September 2019

...so long as they can write the hymnbooks

I took Wednesday afternoon off to attend a do at my daughter's primary school. They had their own World of Wearable Arts show.

For those outside of NZ, the WoW Festival happens annually in Wellington (it used to be in Nelson) and shows of just incredible design skills. I've attended a few times, and it's awesome.

There's sometimes an underlying message in the costumes, but often they're just fun.

The school went for themes for their costumes, but things varied by classroom.

The first classroom had students working in pairs or trios; one or two would read off a description of the work while the other modelled it.

The first classroom had:

My daughter had the Forest Stewardship Council costume - at least that recommendation is pretty sensible, and she hadn't asked my advice on it.

I do wish someone had had a dollar-sign costume in praise of carbon pricing.

For those outside of NZ, the WoW Festival happens annually in Wellington (it used to be in Nelson) and shows of just incredible design skills. I've attended a few times, and it's awesome.

There's sometimes an underlying message in the costumes, but often they're just fun.

The school went for themes for their costumes, but things varied by classroom.

The first classroom had students working in pairs or trios; one or two would read off a description of the work while the other modelled it.

The first classroom had:

- An orange, telling us to make healthy food cheaper;

- A carrot, telling us to make healthy food cheaper;

- A broken television, telling us that we have too much screen time;

- A medley of items telling us how special the sea is and that plastic straws are bad;

- A medley of items telling us that electric cars are important;

- An ambulance telling us about allergies, and that there should be more free ambulances;

- A medley of items telling us that fast food is bad;

- A medley of items telling us that littering is bad and recycling is good and that we should stop having more roads so we can save the environment;

- A medley of items reminding us of the need to stop ocean pollution, perhaps by having more rubbish bins near the beach;

- A medley of items reminding us of the problems of plastic pollution in the ocean, and that we need more recycling.

The second classroom had a very different theme and take. Students again were in trios, with the first student costumed as a material, and the next two costumed as things that come from those materials. The students had some rhyming verse about what they each were - it was nicely done.

These were:

- A tree, followed by wooden items, and by money because money makes people happy (though I'm pretty sure NZ money is made from plastic);

- A tree, followed by an eraser, and wooden items;

- A grapevine, followed by some grapes, and by some wine!

- A gold mine, followed by a gold nugget and a gold weight;

- A sheep, followed by some wool and by a jumper;

- A bird, followed by a feather and then by a feather rug;

- A gold nugget, followed by a gold bar, and then by some jewellery;

- A chicken, followed by an egg, and then by a cupcake.

The third classroom - a combined large classroom - had costumes themed around the topic of global warming.

And here's what they had (often items attached to shirts, hats and masks representing these things), with this being as verbatim a summary as I can provide from the descriptions read by the students

- A costume celebrating walking to school to reduce emissions;

- An electric car;

- An electric car and icebergs;

- A lightning bolt hero for electric cars;

- Melting ice and polar bears

- Solar panels and wind;

- Thunder and lightning because thunder and lightning cause hurricanes and you should buy an electric car;

- A fridge (very well constructed) representing the problems facing the ozone layer and you should stop burning fossil fuels to save the ozone layer;

- Don't use CFCs to save the ozone layer;

- Deforestation: a superhero reminding us that deforestation hurts the ozone layer;

- Deforestation: animals harmed by it;

- A tree reminding us that deforestation is bad;

- A bird encouraging us to use Forest Stewardship Council endorsed products

- Replant trees!

- Landfills are bad: garbage trucks

- Landfills are bad: reuse plastics or don't use them at all

- Plastic pollution is bad: reuse plastics and use fabric bags;

- Plastic is bad; bamboo is good;

- Reuse plastic or use less plastic;

- Reuse plastic or use less plastic;

- A bird reminding us that fabric bags are better than plastic bags;

- Rising sea levels and melting ice caps;

- Rising sea levels are bad, turn down your thermostat to use less energy;

- A monster representing rising sea levels (very well acted).

I do wish someone had had a dollar-sign costume in praise of carbon pricing.

Saturday, 21 September 2019

On the merits of perspective

Me, over in Stuff, with a few helpful numbers that can provide perspective. Perspective is important. If you know a few basic figures about the size of the country, the economy, and government spending, you'll have a better nose for detecting and dismissing nonsense claims.

I lead off with the silly claims about the volume of litter:

That extrapolation generated big big numbers – 10 billion littered cigarette butts around the country, almost 395 million litres of littered disposable nappies, and the like.Uncorrected accounts, as of 21 September, include:

Anyone with a sense of perspective would have known those numbers were fishy.

The government collects just under $2 billion in tobacco excise per year, and excise on a cigarette is just under a dollar per stick, so it's likely around 2 billion cigarettes are smoked in the country per year. Is it likely that a country that smokes about 2 billion cigarettes per year has 10 billion littered cigarette butts strewn about?

Similarly, is it likely that a country where about 60,000 kids are born annually can generate that volume of littered nappies? Suppose a littered nappy is about a litre, and that a baby uses eight nappies per day in its first year. That gives us just over 175 million nappies used by the country's newborns every year. How then is the volume of littered nappies more than double that figure?

Nobody reporting on these figures seems to have a sense of perspective. Fortunately, Keep New Zealand Beautiful has, after no small amount of prodding from me, pulled the dodgy stats from its website and from its report – but has issued no formal correction or retraction. The numbers will live forever in uncorrected newspaper accounts and be cited in uncountable school essays and newspaper articles to come.

- Jamie Morton at the Herald

- Amber-Leigh Woolf at Stuff

- Anan Zaki at RNZ (and here) (and here at NZ Geographic)

- Emily van Velthooven at One News

- Virginia Larson at North & South

I have prodded Morton more than a few times on Twitter on this one, because I expected better of a science reporter. It seems hopeless.

Here are a few more numbers worth memorising. They help in providing a sense of perspective. You can use them when benchmarking claims to see whether they make a lick of sense.Perhaps our newspapers, news magazines, and news broadcasts should come with a health warning label.

New Zealand has about 5 million people. When you see a big number for the country as a whole, dividing it by the population can help check whether the number seems plausible.

New Zealand's Gross Domestic Product (GDP), by the expenditure measure, was just under $300 billion for the year to March 2019. A 5 million population gives us a per capita GDP of about $60,000.

The government's budget for 2019/2020 was just under $111b – the government spends about $22,000 per person. Just over $24 billion is spent on benefits through the Ministry of Social Development, with $15.5b of that going to NZ Super. The total health budget is about $18b. Police get just under $2b. Pharmac is about $1b.

So when you hear claims that alcohol costs $7.8b per year, it becomes immediately obvious the figure isn't a measure of costs to the public health system or police – unless you're happy to believe that alcohol can be blamed for 40 per cent of total government spending in those areas. Rather, the number includes a lot of private costs like spending on alcohol – and as I've previously shown, counts some of those things twice.

New Zealand is a big place: just under 27 million hectares. As of 2012, urban land comprised about 228,000 hectares: only about 0.85 per cent of the country is urban land. So we are in no danger of urban sprawl, or landfills, taking over the whole country.

A moderate, healthy sense of perspective is far from dangerous.

It is vital? Yes, especially when journalists seem to err on the side of having none whatsoever.

Friday, 20 September 2019

Does Market Economics understand either Markets or Economics?

Over in our Insights newsletter, I go through a bit more of the background materials on the government's National Policy Statement on sensitive soils.

I OIAed the supporting cabinet paper, which MPI released after the Ombudsman's office gave them a very helpful hurry-up. Thanks Ombudsman's office!

The rest of MPI's materials are here.

And last week, Treasury passed along their advice on this stuff (another OIA request). I expect it'll be up on their proactive release site in due course; I'll copy some of it below and will get it up at our website if Treasury doesn't have it up soon [okay, here you go].

Here's the column:

LOOKING-GLASS ECONOMICS AND HIGHLY PRODUCTIVE SOILSHere's the really depressing part from the Treasury OIA. Treasury challenged Market Economics, the team of mostly geographers who put together the indicative CBA for MPI, on problem definition. Treasury's Chris Parker notes that the CBA includes no problem definition that includes a market failure to be addressed.

When Alice tried to recite one of her lessons while down the rabbit-hole in Wonderland, she thought only a few words had come out wrong. The Caterpillar corrected her bluntly: “It is wrong from beginning to end.”

By contrast, the Cabinet Paper on the National Policy Statement protecting sensitive soils is not wrong from beginning to end.

Paragraphs 90, 91 and 92 contain sound advice from Treasury.

Otherwise, the paper has a few problems.

About a month ago, the government issued a proposed National Policy Statement allowing councils to designate areas of agricultural land where residential development would be banned.

I warned in Insights it risked undermining the urban growth agenda. Urban land makes up less than 1% of the country by area. It is utterly implausible that urban growth will take over the country’s agricultural land.

The normal operation of markets provides additional protection. The price of agricultural land incorporates buyers’ and sellers’ expectations of the future value that can come from agricultural uses of that land. If turning a paddock or a horticultural block into a subdivision is profitable, that means the services provided by that land in housing are more valuable than the crops that otherwise might have grown there.

So I requested the Cabinet Paper and Treasury’s advice.

Corwin Wallace’s advice from Treasury’s side in the Cabinet Paper is correct and trenchant. The difference in land value on either side of urban-rural boundaries means the land in an 80-hectare farm at that boundary would be worth between $120 million and $182 million more if it were allowed to help solve the housing crisis. Banning that conversion destroys value and risks exacerbating the housing shortage.

Treasury recommended deferring the NPS until a more rigorous cost-benefit assessment had been undertaken, and that the Ministry for Primary Industries be directed to provide options to reduce the risk of the NPS restricting housing supply.

The indicative CBA provided to the Ministry by Market Economics was astonishingly poor. Treasury provided instructive critique. And Market Economics’ response to Treasury revealed such a confused understanding of the concept of market failure that it would have earned a failing grade in the intermediate microeconomics course I once taught.

The NPS on sensitive soils is based on distorted, looking-glass-world economics. Without substantial improvement, it risks pushing us all further down the housing crisis rabbit-hole.

Market Economics replies:

"The "market failure" is quite clear. Highly productive soils which have long term productive and sustainability benefits for the NZ economy and community are being lost as land is taken up for urban uses, and rural residential properties. The nature and structure of the land market means there is no mechanism through which those benefits can be protected and preserved for current and future generations. ... Commercial markets do not have a mechanism where the aggregate loss of soils is taken into account...."

This is hogwash. I expect that MPI wanted hogwash and contracted for hogwash, and was delivered the wanted hogwash - but we shouldn't pretend that this kind of thing passes any kind of bar for counting as economic analysis or a CBA. Whoever contracted it will get a pat on the head from MPI's CE and the Minister for having backfilled the necessary hogwash in support of the Minister's preferred policy rather than being fired for having wasted a pile of money on hogwash.

Let's try to make the best case out of this. There will be sensitive lands that provide ecosystem benefits that are not currently priced. Wetlands come to mind. Agricultural land will sequester some carbon, so that's good.

But there's just absolutely no way that ecosystem services provided by land in intensive horticultural use growing potatoes provides ecosystem services of $1-$2 million per hectare - the ballpark land price differential when land can be turned into housing.

And it's also wrong to say that there's no way for these benefits to be otherwise protected. Here's an alternative policy: pay the owners of land providing valuable ecosystem services an annual subsidy that is no higher than the value of those services. If they're still willing to sell to developers, then the land's more valuable in housing.

And it's also wrong to say that commercial land markets have no way of valuing things when there are lots of small decisions and purchases being made at the margin. That's exactly how markets work: equilibrium prices are the result of all those small decisions and purchases. Lots of small purchases of agricultural land results in the bidding up of the price agricultural land, and especially of larger contiguous blocks of agricultural land if those larger contiguous blocks are differentially more productive. When developers are no longer able to outbid agricultural uses, then the value of the land for agriculture is higher than the value of the land for residences.

Everywhere through this darned stuff you see the assertion that because developers can always outbid agricultural uses, there's inadequate protection of agricultural uses. But that has the whole world backwards. Housing can only outbid where the value of land in housing is higher than the value of land in agriculture. And that can't be an equilibrium phenomenon unless there is already overly strong protection of agricultural land! Otherwise, we would expect people to keep buying land to turn into housing, and that that would happen until the value of land for housing use dropped down to the bare paddock cost.

The fact of the differential instead points to that there is already too much protection of land against being used in housing.

Look, I get mad about BERL's silly work on the cost of alcohol. That nonsense can lead to bad policy around alcohol that imposes needless cost on moderate drinkers. But there are bounds to the losses there. Looking-glass economics applied to land use planning is orders of magnitude more destructive.

This is just so darned depressing. The government seems determined to push this policy through. The most we might be able to hope for is limiting the damage it causes. For example, maybe councils where the median house price is more than 8 times median income could be barred from putting protected designation over more than a very small proportion of their land area.

Minister Twyford used to talk a lot about the importance of letting cities grow up and out, and of abolishing urban growth boundaries. The soils NPS risks entrenching urban growth boundaries in worse form.

Previously: Precious Agricultural Land

Scarcity makes climate change interesting

A couple weeks ago, Paul Gorman asked me what New Zealand could do about climate change in a world where there were infinite resources.

There is no problem with climate change in a world of infinite resources. You could build kit that pulls CO2 from the atmosphere (current cost of pulling carbon out that way is about $100/tonne) and solve it that way - or we could all costlessly flip over to electric cars with enough new costless non-carbon electricity generation to make it all work.

Scarcity makes it interesting because you have to think about trade-offs and getting the most value out of limited resources.

I sent Paul a pretty lengthy answer; he was only able to use part of it in the story for obvious reasons. I gave it more for background, and to help me lay out my own thinking. So I'll copy it here so I can find it later if I need it - and so you can tell me what I've messed up if I've messed anything up.

You’ve specified an uninteresting question. If we had infinite, unlimited resources, then there’s no problem at all. There is existing technology that can scrub CO2 from the atmosphere for about $100/tonne. So if we had infinite money, we could build a pile of those plants and just suck the CO2 out of the atmosphere. Problem solved; next question.On the 'can pull CO2 out of the atmosphere for around $100/tonne' bit, see here on direct air capture.

The problem is only interesting because we have limited resources. And that’s what makes it an economic problem – economics is the science of figuring out how to deal with scarcity.

Here are my starting premises, which I don’t think are at all controversial.

Those are my premises. From those premises, we can derive some conclusions. Some of those conclusions will be controversial. I think they flow directly from the premises and from first-principles in economics.

- Neither the government nor anyone else really knows any individual company or industry’s cost of mitigating GHG emissions. For some companies in some industries, there will be low-hanging fruit where it’s cheap to mitigate, but that is not true for all firms or industries.

- Opportunities for mitigation vary by country. In some places, it’s relatively cheap to reduce GHGs. In others, not so much.

- What makes most sense will depend a lot on what other countries are doing too. When countries do not coordinate, it is easy to wind up in scenarios where GHG mitigation in one country results in greater global emissions because production shifts to places where there production involves more GHG emissions.

- Getting poorer countries to come to the table either requires making low-GHG tech really cheap for them, or carbon-equivalent tariffs to make it as though countries without a price on carbon have one in their export markets, or both.

- Mitigating inequities resulting from any first-best carbon-charging regime is important not just for equity, but also for the durability of any institutions that are built to mitigate GHGs so they aren’t just abolished on the next flip of the electoral cycle.

- Premise 1 tells us that we need to have a price on GHG that allows people to adapt in the ways that makes most sense given their own particular circumstances of time and place. It’s an argument for using either carbon taxes, or a strengthened version of the ETS, rather than command-and-control regulations running sector-by-sector. The government might have guesses about whether it makes the most sense to reduce emissions in transport, or in agriculture, or in industrial heating – but it just can’t really know. Getting a common price for CO2 equivalents across all sectors, comprehensively, is the only way to be sure that we’re doing the most good we can do. Under a carbon price, we encourage abatement activity that costs up to the current carbon price. With regulatory approaches, we risk paying much much more. Like a hundred or a thousand times more – that’s the kind of range of costs experienced in international studies of this stuff. That means that those approaches do 1/100th or 1/1000th as much good as could have been done if the effort had been coordinated through a carbon price instead.

- So: strengthen the ETS. Get agriculture into it, completely, with methane charged as its carbon-equivalent. But be VERY CAREFUL to incorporate the equity considerations in 5, below, and the international considerations in 3, below.

- Premise two tells us that we absolutely have to either have an internationally linked ETS allowing trading in carbon units across countries, or a ‘dirty float’ ETS that sets the ETS cap to target prices in stringent European countries (basically, making sure that carbon prices here are not higher than in Europe). Why? For the same reason as that expressed in (1), above. If we have a carbon price of $25/tonne in New Zealand, and it’s possible to mitigate GHGs in other places for a carbon price of $2.50/tonne, we do only 1/10th as much good by focusing all of our efforts domestically. I’m not kidding here – there’s work suggesting that protecting Amazon rainforest costs less than $1.70USD/tonne for CO2 equivalent GHG effects. That’s about a tenth of the price in New Zealand. Even if that estimate is wrong and the real cost is double, it’s still a fifth of the price in New Zealand. If we care about doing the most good possible on limited resources, we have to be looking for the options that do the most good per dollar spent. Looking only within New Zealand is then a mistake.

- Premise three reminds us that, even if we aren’t considering abatement options that come from efforts abroad, we have to be considering how the rest of the world works when setting up optimal policy here. Agriculture is the most concrete example. In a first-best world, you’d want a common price on CO2 equivalents across everything, and agriculture would be in the ETS. But if agriculture doesn’t face a carbon charge in places where producing milk or meat comes with more GHG, then you wind up reducing emissions in New Zealand while increasing production in worse places overseas. How do you deal with that? Potentially with a regime that has agriculture in the ETS, but with rebates on the ETS charge for exports into markets that either don’t face a carbon charge or where other countries’ goods are sold that don’t themselves face a carbon charge. That will be tricky to set up. But we risk doing harm if we don’t think about it.

- New Zealand is not in a position to force the technology curve in any real ways in transport or electricity – we just don’t have the economies of scale to do it. In other places like the US, there can be productive debates about whether massive government funding into tech around solar panels can make them cheap enough that poorer countries will find them the best option for new electricity generation because they’re cheaper than anything else. Those debates are contentious. But irrelevant for a country like New Zealand except in one area: ag tech. New Zealand research has been working, for some time, on improved pastoral systems for reducing agricultural GHG emissions. That research is hindered by the de facto ban on doing that kind of research in New Zealand. But if anything comes of it, it would be very much worth releasing all of the research, for free, to anyone in the world who wants to use the newly developed ryegrasses. New Zealand’s research funding would then help reduce emissions globally rather than just here. On carbon-equivalent tariffs, those are best considered as part of the OECD rather than something NZ should go it alone on as it’s just too easy for other countries to use those things for protectionist purposes rather than to try to re-create the effects of a carbon price for the products of places that don’t have one.

- Finally, equity. If we are serious about this, and about the durability of ETS institutions over time, our starting point should be an allocation of ETS credits to every existing emitter to cover their status quo emissions over an extended period, then Crown buy-backs of permits through the ETS to get us to the cap. That builds in a just transition so those who flip out of carbon-intensive forms of production to other activities are compensated for the change immediately. Currently, agriculture’s accession into the ETS is a hack-job. Everyone expects that exposing the agricultural sector to a $25/tonne carbon price would bankrupt the sector, so we use fudges that require purchasing credits for only a fraction of emissions. The big problem we have is that the price of agricultural land, often purchased under high leverage, incorporates expectations around whether farms will need to pay for CO2 emissions, for water, or for nutrient emissions. Start imposing carbon charges, water charges, or emissions charges, and all the numbers on which the mortgages are based will fall apart and you’ll have a massive problem. Big numbers of bankrupted farms – farms that played straight by every rule that they ever faced – would be obviously inequitable and would immediately have National promising to tear up the charging regime. If you instead allow a just transition by providing allocation of credits to existing emitters, but having agriculture fully within the regime (subject to 3, above), there wouldn’t be bankruptcies. There’d instead be marginal farms that realise they can make more by shifting to other forms of production and selling their credits back into the system. And that’s a far easier situation to be in – one that’s consistent with ETS institutions that can be binding and real and durable over time.

Implication: it is vastly stupid to enact policy that costs more than $100/tonne to pull CO2 from the atmosphere because we could just build those kinds of plants instead.

Tuesday, 17 September 2019

Keeping up with the state of play on vaping

I was looking around the other day for something like this. The Competitive Enterprise Institute has started tallying up all the reported cases of 'vaping-related' illness in the US.

THC-vaping, and especially illicit vape cartridges, feature prominently, but there are other cases where that's not yet pinned down.

Vaping has been well established in the US for some time. The big recent surge in cases can then be consistent with a few potential hypotheses:

Megan McArdle nails it:

THC-vaping, and especially illicit vape cartridges, feature prominently, but there are other cases where that's not yet pinned down.

As Dr. Konstantinos Farsalinos, a cardiologist, recently wrote, a sudden outbreak in a short period of time and in a specific geographic region (so far this appears restricted to the U.S.) when e-cigarettes have been available and widely used around the world for more than 12 years, is not indicative of disease, but rather of poisoning. That is, it is unlikely that the cause stems from well-established products, but rather from a new product, ingredient, or manufacturing practice affecting products in the illegal market, legal market, or both. It does not, as some argue, prove that e-cigarettes or vaping causes long-term harms.Recall that THC-based vaping is legal in some states, but not others. There are dodgy suppliers of vaping cartridges, often for THC-based product; that THC-based vaping is illegal in some places means there will be dodgy suppliers. Here's a New York Times report on illegal vape cartridges in Wisconsin, where THC is not legal.

On Wednesday the Trump administration said it planned to ban most flavored e-cigarettes and nicotine pods — including mint and menthol, in an effort to reduce the allure of vaping for teenagers. But the move may expand underground demand for flavored pods. And it does nothing to address the robust trade in illicit cannabis vaping products.In normal markets, brand reputation is incredibly important. In illegal markets, having a very popular brand means that you're likely soon to be found and arrested. That makes for very different incentives. In normal markets, you build up brand reputation to be able to run over the long term. In illegal markets, if your brand starts getting popular, you probably need to start thinking about end-game strategies for cashing out as fast as you can.

The Wisconsin operation is wholly characteristic of a “very advanced and mature illicit market for THC vape carts,” said David Downs, an expert in the marijuana trade and the California bureau chief for Leafly, a website that offers news, information and reviews of cannabis products. (‘Carts’ is the common shorthand for cartridges.)

“These types of operations are integral to the distribution of contaminated THC-based vape carts in the United States,” Mr. Downs said.

They are known as “pen factories,” playing a crucial middleman role: The operations buy empty vape cartridges and counterfeit packaging from Chinese factories, then fill them with THC liquid that they purchase from the United States market. Empty cartridges and packaging are also available on eBay, Alibaba and other e-commerce sites.

The filled cartridges are not by definition a health risk. However, Mr. Downs, along with executives from legal THC companies and health officials, say that the illicit operations are using a tactic common to other illegal drug operations: cutting their product with other substances, including some that can be dangerous.

The motive is profit; an operation makes more money by using less of the core ingredient, THC — which is expensive — and diluting it with oils that cost considerably less.

Public health authorities said some cutting agents might be the cause of the lung illnesses and had homed in on a particular one, vitamin E acetate, an oil that could cause breathing problems and lung inflammation if it does not heat up fully during the vaping aerosolization process.

Medium-grade THC can cost $4,000 a kilo and higher-grade THC costs double that, but additives may cost pennies on the dollar, said Chip Paul, a longtime vaping entrepreneur in Oklahoma who led the state’s drive to legalize medical marijuana there.

“That’s what they’re doing, they’re cutting this oil,” he said of illegal operations. “If I can cut it in half,” he described the thinking, “I can double my money.”

That said, it's still ridiculously stupid to draw massive attention to your own product by killing your customers. More likely, the Dank Vapes people didn't think the thickeners would do harm (it's a vitamin; vitamins are healthy!) and figured it was time to cash out.

- Long-term risks are always unknown, and now some folks have been vaping long enough for those to eventuate

- But that would predict a slowly rising number of cases broadly matching the uptake pattern. Instead there's a surge, and a surge that's particular to America and not seen in the UK where vaping is also well-established;

- When millions of people are vaping, random-draw low-probability stuff becomes more likely

- That could be part of the base rate, but also doesn't explain the surge;

- Dodgy suppliers, mostly in the THC market but potentially also in the nicotine market, figured out they could cut product with weird oils and double their money; supply chains of empty cartridges and counterfeit packaging established themselves around the THC market.

I'm still betting on that dodgy suppliers explains most of this mess.

Megan McArdle nails it:

At this point, the best information suggests that a recent spate of deaths from a vaping-related lung disease — six at last report — had little or nothing to do with legal e-cigarettes. Rather, the deaths, and more than 300 confirmed cases of the disease in dozens of states, seem to be linked to illegal cartridges, mostly using marijuana derivatives that had been emulsified with vitamin E acetate, according to Food and Drug Administration investigators. The FDA has warned against using it for inhalation, and it isn’t used in legally manufactured e-cigarettes.Meanwhile, Radio New Zealand is running every scare story it can find on vaping, and providing none of the necessary context about the illicit THC market. I absolutely do not envy the folks over at MoH having to deal with the political pressure caused by RNZ's driving of a moral panic.

Naturally, the government wants to ban legally manufactured e-cigarettes.

Monday, 16 September 2019

Explaining the Outside of the Asylum

I had a chat about NZ as the Outside of the Asylum with the Heritage Foundation's Timothy Doescher when he was in town recently.

The podcast is available here. You can also catch it at Heritage's website, where it has the links to Spotify and other versions of it.

My Outside of the Asylum piece, on which the conversation was based, is here.

The podcast is available here. You can also catch it at Heritage's website, where it has the links to Spotify and other versions of it.

My Outside of the Asylum piece, on which the conversation was based, is here.

Friday, 13 September 2019

Job Openings for Economists - Spotify edition

This would be a heck of a lot of fun for somebody.

Econ lecturers: be sure to note this as one of the interesting places that a solid economics degree can take you.We are looking for an outstanding Head of Economics to join Spotify’s Content team. Our mission is to unlock the potential of human creativity by giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their work and billions of fans the opportunity to enjoy and be inspired by it. Are you a creative thinker who can combine a strong economic toolbox with a desire to learn from others, and who knows how to execute and deliver on big ideas. You would be working across the content teams and with many other related departments, providing economics, statistical and policy support that enable evidence-based decision making to help Spotify achieve its stated goal.What you’ll do

- You will be working horizontally across the company, from markets to marketplace and licensing to policy.

- You will be working closely with cross-functional teams across the company on complex and unprecedented problem-solving challenges that require fast turn-around solutions.

- You will be able to learn quickly and apply all relevant excel, coding and query skills available within the company, and to be able to build user-friendly tools on top of those data platforms

- You need to be able to present economic analysis clearly and concisely to both internal and external audiences who are not trained in the subject, including media.

- Work from our New York or London office, with occasional travel.

Who you are

- You have 7-10 years experience with a strong understanding of economics within the broader media and tech industries.

- You have 3+ years experience managing a team.

- You have excellent statistical training and a proven track record in constructing excel models (such as long tail analysis) for solving problems that are without precedent.

- An MSc (or above) economics training at a reputable university with a research background in applied macro and microeconomics, and proven modelling skills.

- Applicants with considerably more experience are encouraged to apply.

- You have a proven ability to commission and project manage large research projects.

It is a plus if you

- Have experience in the music industry.

- Can demonstrate how you retain objectivity in your analysis and communication.

- Love working a dynamic and fast-moving environment

- Possess effective verbal and written communication skills.

- Have the technical competence to perform more advanced analytics:

- Analytics tools experience (such as Tableau)

- Experience performing analysis with large datasets

- Knowledge of conjoint software (i.e. Sawtooth) and other pricing tools

A rubbish clean-up

That rubbish set of stats over at the Keep New Zealand Beautiful website, noted earlier this week, is now corrected.

The National Litter Audit website has been purged of the bogus numbers, and the report updated.

This is good.

Unfortunately, in the absence of any more formal retraction or notice from them to the journalists that reported so credulously on the figures, we're unlikely to see either any correction or any updated stories noting the figures are wrong.

The National Litter Audit website has been purged of the bogus numbers, and the report updated.

This is good.

Unfortunately, in the absence of any more formal retraction or notice from them to the journalists that reported so credulously on the figures, we're unlikely to see either any correction or any updated stories noting the figures are wrong.

Minimum wages and piece-rate work

Piece-rate payment for work can make a lot of sense when it's easy to observe output, hard to observe effort, and effort can yield substantial differences in worker output. It's been common in some agricultural work, especially fruit-picking.

This tweet from last year somehow crossed my stream this week. Jennifer Doleac last year tweeted the job-market papers of female economists out on the job market. And this paper struck my eye:

Dr Hill is now Assistant Prof in Ag Econ at Colorado State - excellent.

The paper shows what happens when a minimum wage sets a lower bound on wages payable under piece-rate work.

Suppose you think that you'd have to exert a lot of effort to make more than the minimum wage under piece-rate, and that you could get away with a lot less effort while not being fired. In that case you may prefer to exert less of that costly effort and get your backstop wage - the minimum wage.

If the minimum wage increases, or at least increases by more than any inflation adjustment to the piece-rate paid, more workers will be discouraged from putting in that effort. Hill shows that a three percent increase in the minimum wage reduces the average worker's productivity by seven percent.

But the paper goes beyond that with some nice theoretical testable results. Like that there'll be a range of income from piece-rates just above the minimum wage that will never be observed, because people will always prefer putting in minimum effort and getting the minimum wage to putting in more effort to get a small amount above the minimum.

The point of a minimum wage in piece-work is to ensure that employers aren't exploiting vulnerable workers. If the most a worker could hope to earn under a piece-rate is less than the minimum wage, and the worker is stuck there after having shifted out to the region because Work and Income insisted they take a job, that's not so hot.

So what to do? A few years ago, we did some work suggesting allowing regional variation in policy, in accordance with local needs. One idea I'd had at the time was allowing a modified version of the minimum wage for piece-rate employers in regions with a lot of fruit-picking.

The modified version would work as follows.

Any employer providing piece-rate pay would be deemed compliant with the minimum wage if at least 80% (say) of its workers on piece-rate were earning at least 125% (say) of the minimum wage. If the vast majority of workers earn a margin over the minimum wage on piece-rate, then it's hardly some sham piece-rate. If you're failing to earn at least the minimum wage while 4/5 of your coworkers are, on piece-rate, the remaining problem is likely you rather than your employer.

So even if some workers didn't wind up earning the minimum wage, that would be their problem rather than the employer's so long as most other workers were earning a margin over the minimum wage.

That kind of scheme could also hit some of the concerns MBIE tends to have about allowing seasonal workers to come in. It's less plausible that seasonal workers are driving down wages if the employer's complement of workers is still earning that margin over the minimum wage.

This tweet from last year somehow crossed my stream this week. Jennifer Doleac last year tweeted the job-market papers of female economists out on the job market. And this paper struck my eye:

Alexandra Hill— Jennifer Doleac (@jenniferdoleac) October 28, 2018

JMP: "The Minimum Wage and Productivity: A Case Study of California Strawberry Pickers”

Website: https://t.co/moA0aKztz9 pic.twitter.com/13kGc244th

Dr Hill is now Assistant Prof in Ag Econ at Colorado State - excellent.

The paper shows what happens when a minimum wage sets a lower bound on wages payable under piece-rate work.

Suppose you think that you'd have to exert a lot of effort to make more than the minimum wage under piece-rate, and that you could get away with a lot less effort while not being fired. In that case you may prefer to exert less of that costly effort and get your backstop wage - the minimum wage.

If the minimum wage increases, or at least increases by more than any inflation adjustment to the piece-rate paid, more workers will be discouraged from putting in that effort. Hill shows that a three percent increase in the minimum wage reduces the average worker's productivity by seven percent.

But the paper goes beyond that with some nice theoretical testable results. Like that there'll be a range of income from piece-rates just above the minimum wage that will never be observed, because people will always prefer putting in minimum effort and getting the minimum wage to putting in more effort to get a small amount above the minimum.

In this paper, I use a theoretical model to show how, under this compensation policy, increases in the minimum wage can affect productivity. In particular, I show that for some workers the wage floor removes the incentives provided by the piece rate and creates the opportunity to shirk, i.e. to reduce effort a lot in exchange for a little decrease in pay. In the empirical application, I find evidence that supports the theory. My analysis follows the productivity of workers over two separate harvest seasons during which the employer raises the minimum wage and the piece rate. I show that in both seasons, minimum wage increases cause workers to slow down and piece rate increases cause workers to speed up. Both changes in the minimum wage are roughly three percent increases and cause the average worker to decrease productivity by seven percent. The piece rate is increased several times in both seasons, allowing for estimation of a piece rate-productivity elasticity. I estimate elasticities that range from 1.2 to 1.6. These suggest that a four to six percent increase in the piece rate would offset the productivity losses from the observed minimum wage increases. I replicate this analysis over a season with no changes in the minimum wage and find precise estimates of no effect from placebo increases and similar estimates of the piece rate-productivity elasticity (1.5 to 1.6)....

I find evidence that employers can offset these losses by raising the piece rate. Estimates indicate that a four to six percent increase in the piece rate would offset the productivity losses from the examined increases in the wage floor. Though outside the scope of this paper, there are other strategies for mitigating these productivity losses. For example, employers may consider alternative contract structures or adopting new technologies that enhance productivity. Piece rate pay has well documented productivity gains compared with hourly pay, but alternative contract structures, such as hourly wages with daily, weekly, or seasonal bonuses, provide comparable incentives. Another potential strategy comes from technological innovation. The productivity decreases I find are an effect of piece rates and productivities that are low enough so that the minimum wage is desirable for some workers. Employer practices that increase productivity by lowering worker disutility from exerting effort are clear options for mitigating these effects. Technological innovations, such as picking assist for strawberry harvesters, are one way employers can do this. Future research can build on this by examining the economic viability of alternative compensation policies and mechanization for reducing the productivity effects from minimum wage increases.So, in short, a minimum wage has some weird interactions with piece-rate work. Piecework provides incentives to supply effort. A minimum wage increase removes that incentive not only for anyone whose piecework effort would result in piecerate wages no higher than the minimum wage, but for a lot of people above that margin: the extra earnings in the interval above the minimum wage aren't worth the extra effort that needs to be expended all the way though. So the piece-rate paid also has to increase.

In the next few years, the California minimum wage is scheduled to increase incrementally until reaching $15 per hour, a 40 percent increase from current levels. My results suggest that the farmer I study will need to increase the piece rate by 50 to 80 percent to prevent productivity losses from these minimum wage increases. Though my results are unlikely to translate linearly to large, statewide policy changes, these predictions are not unreasonable. Based on the productivity and piece rate in the 2015 season, the piece rate would need to increase by 20 percent for the average worker to earn $15 per hour. These piece rate increases can prevent productivity losses, but will substantially raise the marginal cost of producing strawberries. This farmer, and many other employers in low-wage industries who pay by the piece, face substantial increases in payroll costs from rising state minimum wages.

The point of a minimum wage in piece-work is to ensure that employers aren't exploiting vulnerable workers. If the most a worker could hope to earn under a piece-rate is less than the minimum wage, and the worker is stuck there after having shifted out to the region because Work and Income insisted they take a job, that's not so hot.

So what to do? A few years ago, we did some work suggesting allowing regional variation in policy, in accordance with local needs. One idea I'd had at the time was allowing a modified version of the minimum wage for piece-rate employers in regions with a lot of fruit-picking.

The modified version would work as follows.

Any employer providing piece-rate pay would be deemed compliant with the minimum wage if at least 80% (say) of its workers on piece-rate were earning at least 125% (say) of the minimum wage. If the vast majority of workers earn a margin over the minimum wage on piece-rate, then it's hardly some sham piece-rate. If you're failing to earn at least the minimum wage while 4/5 of your coworkers are, on piece-rate, the remaining problem is likely you rather than your employer.

So even if some workers didn't wind up earning the minimum wage, that would be their problem rather than the employer's so long as most other workers were earning a margin over the minimum wage.

That kind of scheme could also hit some of the concerns MBIE tends to have about allowing seasonal workers to come in. It's less plausible that seasonal workers are driving down wages if the employer's complement of workers is still earning that margin over the minimum wage.

Thursday, 12 September 2019

Radio NZ on vaping, again

The Washington Post notes the growing consensus around just what the heck is going on with 'vaping-related' illness and death. Like I'd said last week, dodgy additives in THC vapes look to be the issue. You don't have to be paying massive attention to this file to know this.

Oregon health officials said last week that a middle-aged adult who died of a severe respiratory illness in late July had used an electronic cigarette containing marijuana oil from a legal dispensary. It was the first death tied to a vaping product bought at a pot shop. Illinois and Indiana reported deaths in adults but officials have not provided information about their ages or what type of products were used.I like that the Post uses the basic plausibility check. If this really were about nicotine vaping, which has been around for a long time, why would there suddenly be a pile of hospitalisations? This is new over the past year. They might yet find cases that look certain to be nicotine-only, but it's a tough one to prove: they've certainly found dodgy stuff in the THC cartridges that sick folks have brought with them to hospital, but not everyone who has used a THC cartridge will want to admit to it.

State and federal health authorities are focusing on the role of contaminants or counterfeit substances as a likely cause of vaping-related lung illnesses — now up to at least 450 possible cases in 33 states.

Officials are narrowing the possible culprits to adulterants in vaping products purported to have THC.

The sudden onset of these mysterious illnesses and the patients’ severe and distinctive symptoms have led investigators to focus on contaminants, rather than standard vaping products that have been in wide use for many years.

One potential lead is the oil derived from vitamin E, known as vitamin E acetate. Investigators at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration found the oil in cannabis products in samples collected from patients who fell ill across the United States. That same chemical was also found in nearly all cannabis samples from patients who fell ill in New York in recent weeks, a state health department spokeswoman said.

On Monday, New York state officials said they are issuing subpoenas to three companies the department has identified as selling “thickening agents” containing high levels of vitamin E that can be used in black market vaping products that contain THC. Dealers have been using thickening agents to dilute THC oil in street and illicit products, industry experts said.

The best advice remains to buy your vaping product from a source you can trust. And to follow Michael Siegel (Twitter) and Clive Bates to keep up with the state of play. I like Action on Smoking and Health NZ, but they haven't really been putting up updates on the US state of play.

Meanwhile, here's how Radio NZ has continued to play the story.

US President Donald Trump has announced that his administration will ban flavoured e-cigarettes, after a spate of vaping-related deaths.Everything in the RNZ reporting makes it seem that the illness is around e-cigarettes rather than vaped dodgy THC.

Mr Trump told reporters vaping was a "new problem", especially for children.

US Health Secretary Alex Azar said the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would finalise a plan to take all non-tobacco flavours off the market.

There have been six deaths across 33 states and 450 reported cases of lung illness tied to vaping.

Many of the 450 reported cases are young people, with an average age of 19.

Michigan this month became the first US state to ban flavoured e-cigarettes.

Joining Mr Trump at the White House on Wednesday, Mr Azar said it would take the FDA several weeks to distribute the new guidance on e-cigarettes.

I expect this is deliberate. It is lying through omission. So I've put in another complaint, this time around accuracy.

RNZ has been on a campaign against vaping for some time. RNZ demonised Marewa Glover's harm reduction efforts. They gave ample airtime to attacks on her. Their reporting on vaping is consistently conflating illness in the US due to dodgy and counterfeit THC product with the kind of vaping people in NZ are familiar with. And they are doing it when the regulatory framework is soon to be announced, helping to fuel a moral panic that will lead to worse regulatory outcomes.

I don't know why RNZ is like this. But RNZ is like this. I wish that I weren't compelled to pay, through my taxes, for their dishonest reporting.

Wednesday, 11 September 2019

The Joyful Contrarian

Reason Magazine has a wonderful tribute to Gordon Tullock by Michael Munger. The steering wheel with the spike on this blog's masthead? That's the Tullock Spike.

What kind of crank wants to put bayonets in steering wheels, praises political corruption as "working out rather well," and thinks that competition can be harmful and should be discouraged? Gordon Tullock, the late George Mason University professor of law and economics, made all those arguments with a (more or less) straight face, while also helping invent the then-new discipline of sociobiology. His insights have proven to be more durable, and more sensible, than his many critics expected.A superb must-read, filled with insights. Go read!

To be fair, economists tend to value counterintuitive arguments, where surprising conclusions emerge from innocuous assumptions. In 2019, we will pass the 70th anniversary of the Communist takeover of China, an event that Tullock witnessed in person from the vantage point of his diplomatic post in Tientsin. That experience launched his thinking about the problem of governance, anarchy, and the importance of rules. Looking back, many of the insights that powered his work from that time—once dismissed not just as counterintuitive but as outlandish—have now become conventional wisdom.

There are lots of contributions worth examining, including his work on voting, bureaucracy, and constitutional theory. But those fit reasonably well into the "public choice" tradition, which Tullock helped found, and are easily accessible to those interested in that approach. I will consider three of Tullock's less well-known, but probably even more important, insights—regarding safety regulation, corruption, and the rationality of evolved behaviors—and see how this work has stood the test of time. The three are very different, but they are unified by one feature that is the hallmark of the economic approach: In every case, Tullock reached a conclusion but pressed further to ask, "And then what?"

Tuesday, 10 September 2019

Rubbish statistics - Updated

UPDATE: it looks like KNZB has quietly retracted the dodgy stuff. Original post follows below, then update and comment.

I caught this rubbish floating around last week - new figures purporting to represent the amount of littering that goes on in New Zealand.

Here's the infographic that Keep New Zealand Beautiful put up to go with their report.

KNZB needs to withdraw its Very Big Numbers, and, if they want to have a number that might represent the country as a whole, work with Stats to find a better way of doing that. In the absence of KNZB doing that, Stats really should withdraw its imprimatur from the report.

* Unless that number comes from anyone associated with Big Industry (tobacco, sugar, alcohol - whatever). Then even accurate numbers are dismissed out of hand, because innumeracy means leaning on trusting the source because you have absolutely no clue how to judge whether a number is right or not.

Update: Thomas Lumley makes similar points.

Update 2: I was in touch with KNZB about this prior to having posted, as well as with Stats NZ. KNZB showed no interest in correcting things, so I posted on the issues.

It looks like they've now quietly retracted the bogus stats.

The National Litter Audit page no longer contains the infographic (though it's still around, unlinked, on the back-end, here). The original link to the report no longer works; this new version doesn't contain the rubbish stats.

It's good that they've fixed it, but there's been no official retraction of the dodgy parts that I can see. So it's pretty low odds that the prior news stories will put up updates correcting anything. Alas.

I caught this rubbish floating around last week - new figures purporting to represent the amount of littering that goes on in New Zealand.

Here's the infographic that Keep New Zealand Beautiful put up to go with their report.

The numbers didn't make any damned sense on the face of it.

Headlines talked about there being ten billion littered cigarette butts around the country. But anyone with a passing familiarity with any of the relevant numbers should have been sceptical. To a first order approximation, the government collects about $2 billion per year in cigarette excise taxes, and the tax on each cigarette is about a dollar. So that's about two billion cigarettes sold per year in total - as a rough estimate. Every one of those cigarettes would have to have been littered, for five years, for that number to make sense. Or half of them littered over a decade, and all of them persisting through to today. Does that seem plausible? I'm happy to buy that a pile of cigarette butts wind up littered, but these numbers sound implausible.

And 395 million litres of littered disposable nappies? Suppose that each diaper is a litre. And suppose that every baby in the country goes through five per day in their first year, four per day in their second year, two per day in their third year, and none per day after that until they start voting for New Zealand First. That would be about 4000 diapers per kid over those three years. Let's round it up to 5000 to make for round numbers. Round numbers are easier.

395 million litres of diapers, at one litre per diaper, would be the output of 79,000 children from birth through toilet training.

There are about 60,000 children born per year.

So every diaper ever used by every kid born over a 16 month period would have to be littered for that statistic to be true. Or half of all diapers used for every kid born over a 32 month period, or a quarter of all diapers used for every kid born over a 64 month period - and with all of the diapers persisting.

Does that make any kind of sense? Does it seem plausible? How innumerate do you have to be to think that this is possibly true?

All results were quoted against a 1000 m2 site area and extrapolated across the area of New Zealand.

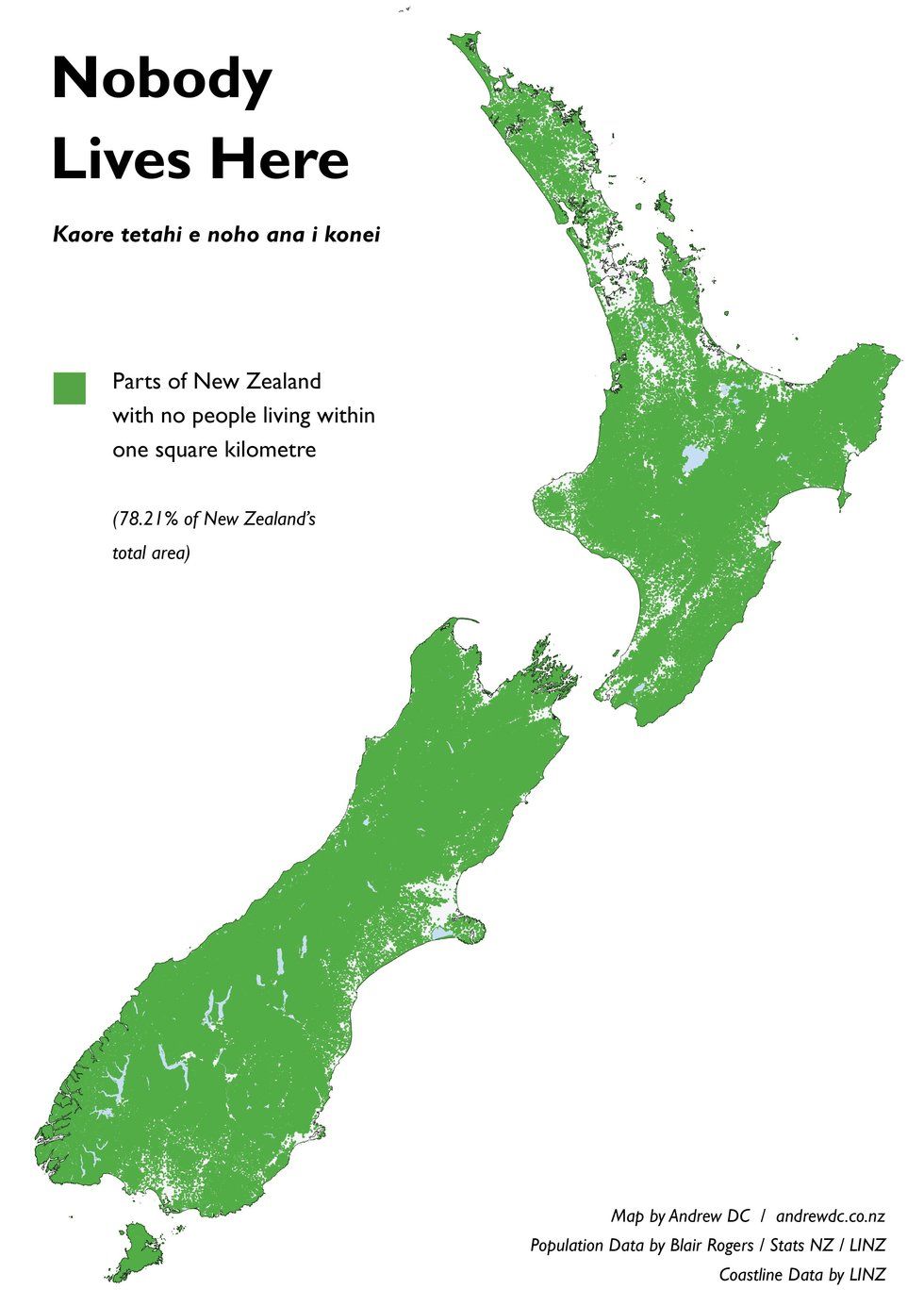

A huge proportion of New Zealand is uninhabited and inaccessible. Remember that map that was making the rounds a while ago, showing all the parts of New Zealand where nobody lives?

If you sample a few sites from the less than 1% of New Zealand that's urban, and then the busier parts of the rest of the country (roadsides, industrial sites, car parks, retail sites, public recreation areas and the like) and then extrapolate to the 99% of New Zealand that isn't urban (including the 78% where nobody lives), you're going to overestimate things.

There aren't obvious problems in their site stocktakes, it's the extrapolation to the rest of the country that's a huge and obvious problem. Anybody who is half-way numerate should have been able to tell that the Really Big Numbers presented for the whole country couldn't be right. But the numbers look authoritative. And Keep New Zealand Beautiful advertises that Stats NZ helped in developing the audit (presumably the sampling, and not the aggregation - there's no way that Stats would have recommended doing this).

And so we got reporting like this:

The project, conducted by not-for-profit organisation Keep New Zealand Beautiful, took five months to complete.

With the help of the Department of Conservation, Statistics NZ and the Ministry of Environment, two leading researchers pegged out areas across the country and calculated their litter content.

Keep New Zealand Beautiful's chief executive, Heather Saunderson, says the results are frustrating.

"The research estimates 10 billion cigarettes are littered across the country. That equates to 2142 cigarette butts per New Zealander."

Enough takeaway containers - 258,043,800 litres worth – were found to fill 25 rugby fields one metre high, while the 364,965,000 litres of disposable nappies was enough to take up 154 Olympic swimming pools.Bad policy comes from bad public perceptions of the true state of the world. Bad public perceptions of the true state of the world are fostered by innumerate journalists who haven't the time to think critically at all about any number presented.*

Despite drops in smoking rates, discarded cigarette butts remained a big headache: some 10,269,090,000 were picked up, or 2,142 for every person in the country.

KNZB chief executive Heather Sanderson said, at railway sites around New Zealand, nearly 12 litres of litres of litter was being found every 1000 square metres.

"Extrapolated, that means 265,324,848 litres of illegal dumping – enough to fill 2,123 rail carriages, which if you stack them on top of each other, would be as high as 151 Sky Towers."

KNZB needs to withdraw its Very Big Numbers, and, if they want to have a number that might represent the country as a whole, work with Stats to find a better way of doing that. In the absence of KNZB doing that, Stats really should withdraw its imprimatur from the report.

* Unless that number comes from anyone associated with Big Industry (tobacco, sugar, alcohol - whatever). Then even accurate numbers are dismissed out of hand, because innumeracy means leaning on trusting the source because you have absolutely no clue how to judge whether a number is right or not.

Update: Thomas Lumley makes similar points.

Update 2: I was in touch with KNZB about this prior to having posted, as well as with Stats NZ. KNZB showed no interest in correcting things, so I posted on the issues.

It looks like they've now quietly retracted the bogus stats.

The National Litter Audit page no longer contains the infographic (though it's still around, unlinked, on the back-end, here). The original link to the report no longer works; this new version doesn't contain the rubbish stats.

It's good that they've fixed it, but there's been no official retraction of the dodgy parts that I can see. So it's pretty low odds that the prior news stories will put up updates correcting anything. Alas.

Don't hate the council, hate the game

Labour's talked a good game around solving the housing crisis. But unless they manage to have councils see growth as being in councils' interest, it's all a bit hopeless. There are always margins on which councils can stymie growth, if they want to.

I'd covered the problem in my fortnightly column over at Newsroom.

Fundamentally, the housing crisis emerged because not enough houses were being built. Not enough houses were being built because council zoning rules prevented sufficient building. This had systematic effects across the whole building industry. Because building vast new subdivisions, or substantial new dense and intensive brownfield developments, was effectively impossible, the construction sector geared up for the task it was allowed to undertake: bespoke small-scale construction and renovation.Today, the Dom reports on one of the standard ways that councils can block growth: go-slows on consenting. I don't know how many times I've heard pious central government officials at MBIE assure me that because councils have to issue consents within a deadline, there can't be any problem. They utterly fail to think about incentives.

Why do many councils facing growth pressures set rules that make it tough to build? Because growth is costly for councils. Councillors face persistent NIMBY opposition to new development. Density advocates work to block surburban expansion while downtown residents opposed to development next door blocked density. The outcome in too many cities was that no one was allowed to build anything anywhere.

But it is worse than that. When an urban council at its debt limit has to accommodate growth, the costs simply outweigh the benefits. Central government gets more income tax revenue when a city’s population expands; local government gets an infrastructure bill. Central government gets more GST and company tax revenue when it allows more commercial and industrial development; local government gets the complaints about tall buildings blocking views and faces the bill for trunk infrastructure upgrades downtown. More rates revenue simply is not enough for councils to make growth viable for them.

It gets even worse. Construction costs are higher than they need to be because of a nest of regulations, liability rules, and incentives. There are, in theory, ways of importing a containerload of gib board from places whose standards we trust and whose challenges are comparable – like Vancouver, Seattle and Tokyo – places that face earthquake risk and wet weather issues.

But council has to sign off on the final building certificate. If council signs off on a building certificate and something goes wrong a decade from now, when every one of the construction companies has flipped from Bill’s Construction (2019) Ltd to Bill’s Construction (2025) Ltd, council is the one left holding the bag under joint-and-several liability. So councils try to limit risk by being highly risk averse about allowable building methods. Standard ways of fixing walls to frames are defined in terms of standard materials. And good luck getting your new build signed off if you haven’t used those standard methods.

Once you recognise the incentives at play, you start recognising the difficulty of the problem – and start seeing the ways of unwinding the mess.

Fundamentally, growth has to be in councils’ interest. If it is not, everything else is futile.

The Dom's Bonnie Flaws is sharper, going through the ways councils can extend deadlines, and why they do it.

However, Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) building system assurance manager, Simon Thomas said that it did not currently collect information on RFIs [Requests for Information: the way of dragging out a consenting process by asking the builder or architect for more information on the deadline day - kinda like dragging out an OIA at the ministries, but no Ombudsman] as a matter of course, and nor did International Accreditation New Zealand, the body appointed by MBIE to carry out accreditation assessments of Building Consent Authorities.

Hunter said that the "poor plans" excuse was unfair.

"I've done thousands of houses, you know. You'd think that after a while with all the RFIs we'd start getting them right. Why are we still getting different RFIs back? It doesn't make any sense," he said.

Institute of Architects Auckland branch chair, Ken Crosson said that councils had become the "last man standing" after the leaky house crisis.

"What we've got now are very gun-shy councils and a building sector beset with problems largely because of poor legislation," he said.

Joint and several liability was a real problem for councils who had picked up costs disproportionate to their liability in the leaky homes saga, resulting in an environment of "super-caution".

Crosson said the cost of consent was exorbitant, and added that any delay resulted in further costs.

"The holding cost on land is enormous, just enormous,'" he said.

Monday, 9 September 2019

Don't get your vaping news from Radio New Zealand

There have been a lot of news reports out of the United States over the past month on people coming down suddenly with severe lung problems, with those news reports often linking the problems to vaping.

Sometimes the story would note that the vaped substance wasn't the typical nicotine e-liquid, but rather a THC-based one. And even more rarely the story would note that the THC cartridge had been purchased from a strange street dealer, or was counterfeit.

More stories started coming out noting that the problem-causing e-liquids were dodgy-as. They were often finding vitamin E in them as a thickening agent. I was seeing a lot of those stories come out last week.

The media reports in the States were fodder for a lot of scaremongering. Most stories didn't note just what was vaped. Where it was a younger person who fell ill, there was little checking of claims of that the vaped substance was nicotine rather than a dodgy back-alley THC cartridge.

And all of that fuels demand for tighter regulation of normal nicotine e-liquids.

The Washington Post finally caught up with the play last week:

State and federal health officials investigating mysterious lung illnesses linked to vaping have found the same chemical in samples of marijuana products used by people sickened in different parts of the country and who used different brands of products in recent weeks.Now there's still work to do in checking that that's what's causing the problems, but Prof Siegel seems to have a smoking gun here:

The chemical is an oil derived from vitamin E. Investigators at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration found the oil in cannabis products in samples collected from patients who fell ill across the United States. FDA officials shared that information with state health officials during a telephone briefing this week, according to several officials who took part in the call.

That same chemical was also found in nearly all cannabis samples from patients who fell ill in New York in recent weeks, a state health department spokeswoman said.

There has been a major breakthrough in the investigation of the outbreak of more than 300 cases of a "mysterious" lung disease that the CDC and many other health agencies have told the public is due to the vaping of electronic cigarettes. And now, everything is starting to make some sense.

Illicit THC vape carts that were obtained from a number of case patients that were tested in federal and state laboratories have tested positive for vitamin E acetate, an oil that just started to be used late last year as a thickening agent in bootleg THC vape carts. Apparently, for every single case in New York State for which testing is complete, vitamin E acetate was found in at least one of the THC vape carts that were used by the patient. Almost simultaneously, testing of recovered THC vape carts by the FDA revealed vitamin E acetate in 10 of 18 tested samples. Importantly, the FDA reported that it found no contamination in any of the nicotine e-liquids tested.

The Rest of the Story

While there are still a lot of unknowns, the pieces of the puzzle are just beginning to fit together. One the great mysteries about this outbreak is "Why now?" Nicotine e-liquids have been on the market for many years and are being used by millions of vapers but there has never been a problem. Something must have changed to result in the outbreak occurring at this time. But what?

Now there is a possible explanation: it turns out that there was a major change made in the bootleg THC vape cart drug dealing industry late last year. It appears that a new thickening agent started to be used in bootleg THC vape carts. Very possibly, that new agent was vitamin E acetate. Tocopherol acetate (the fancy name for vitamin E acetate) is a thickening agent that is typically used in cosmetics like skin cleansers. But late last year, it apparently began to be used for thickening the THC oil (presumably to hide the fact that it had been highly diluted, which is a clue to some buyers that they are not getting much product). Here is what leafly.com has to say:

"Peter Hackett of Air Vapor Systems and Disinger and Heldreth of True Terpenes both mentioned the recent introduction of a novel diluent thickener called Honey Cut. The product swept through LA’s pen factories late last year. Honey Cut maintains a website, but the identity of the product manufacturer remains unknown, as does the chemical makeup of the substance. Leafly has made many attempts to reach officials at Honey Cut, but they have chosen not to respond.Honey Cut’s introduction last year proved so popular that competing products by other diluent makers soon began appearing."

What was the new diluent thickener in Honey Cut?

You guessed it ... tocopherol acetate.

Siegel started warning about this mess in late August.

This stuff is or ought to be common knowledge among anyone half-way paying attention to the vaping file.This emerging story shows the dangers of bias in public health. The long-standing bias of the CDC against vaping has resulted in the agency failing to warn the public in clear and specific terms about the risks associated with the use of bootleg THC vape carts and instead, issuing warnings against "vaping" and "e-cigarettes" generally and making meaningless statements like "e-cigarette aerosol is not harmless water vapor."