When I see something I think is stupid, if I'm not being too intemperate, I try to ask myself, "What is the least stupid argument that could have led to this view?" Steelmanning an argument, rather than strawmanning it, just makes more sense.

It could be that the person making the argument is saying something subtler than it sounds like. Or it could be that the person heard the conclusion from someone smarter than himself, never understood the argument, but there is a logic that the prior person had that can be rediscovered.

Max Rashbrooke really doesn't do this when it comes to the Emissions Trading Scheme.

His latest piece on the ETS misrepresents how the ETS works, and my outfit's position on it.

Let's go through.

If the price of petrol continues to soar, will you be able to seamlessly shift to taking the bus instead? On such questions hangs the fate of the climate change fight.

Outright deniers having been banished to the fringes, the debate now turns on how best to reach net zero by 2050.

And while most observers believe a wide range of tools will be needed, a rearguard effort is being fought by those who would deploy just one lone policy: putting a price on carbon.

If, the argument runs, everyone has to pay a price for their carbon pollution – $100 a tonne, say – they will automatically cut their emissions. And, knowing their options far better than Beehive bureaucrats, they will find the cheapest method possible.

So far so good, except that he's insinuating that those wanting to rely on carbon prices are secret climate change deniers.

One bit to watch for: no supporter of the ETS has some magic price figure in their head. They don't have to. A carbon tax requires picking the right price. The right price, for economists, for a carbon tax, is the price that matches the marginal social cost of the emission. It isn't the price that forces everyone to stop doing one particular thing. Put the price on carbon, so that if someone does the thing that causes the emission, they've weighed the social cost of the emission in their own calculus - or at least are providing potential compensation for that cost.

An ETS does not require picking the right price. It does require that every tonne of emissions within the covered sector is backed by the surrender of a credit. Our ETS does that. Net emissions in any year cannot exceed the sum of the credits that the government issues that year (those auctioned plus those allocated to industrial users), plus the units purchased in prior years but not yet surrendered. The price winds up being an outcome. "Getting the price right" should just mean that the ETS market works well, that the credits are credible, and the system is binding. Whatever price emerges from that process is the right price.

I'll tweak that a bit later when coming to linkages to international markets, but let's keep it simple for now.

Let's continue.

Such views are a throwback to 1980s-style market fundamentalism, which held that almost all problems can be solved by individuals buying and selling things. It is a largely discredited dogma.

Yet the old cry of “just get the prices right” still echoes in some corridors.

The New Zealand Initiative think-tank, scion of the 1980s right-wing icon the Business Roundtable, recently published a report accusing the Government of committing “fraud” simply by promoting other climate policies, like enhancing public transport.

It's gotten a bit worse. It is odd to call either a carbon tax or an ETS market fundamentalism. Either one is a hefty government intervention with implications across the entire span of the economy.

And again, with an ETS, as compared to a carbon tax, there's no right price. The price emerges. Whatever price emerges is the right price. Don't like that price? Cut the cap faster and the price will be higher. But if the price winds up being higher than in other places that take carbon seriously, you've likely mucked something up - and a linkage to international markets is probably going to be needed.

We've critiqued government policies that aim to reduce net emissions within the covered sector. Enhancing public transport, if done to reduce net emissions, will not work. But rising carbon prices will change demand for modes of transport - and lots of other things as well. If a council's best forecast is that residents are going to want a whole lot more public transit as consequence of those rising prices, then council absolutely should be factoring that into their planning.

I've regularly described this as the difference between pushing on a rope and pulling on it. If you push on it to try to reduce emissions, it won't work. But if higher prices are pulling the rope, and councils are seeing that translate into changing expected demand for transport and other services, then council should accommodate it the same way they would other changes in residents' demand.

The report’s author, Matt Burgess, now works for National leader Christopher Luxon. Which creates problems for the party.

Last month, its climate change spokesperson, Scott Simpson, had to publicly disavow the Burgess report, saying it “does not reflect the National Party’s view”.

Think-tankers can think all they like; Simpson has to get elected by a public that wants governments to actually do something on climate, not just attach price labels.

The Burgess report, though, is backed by ACT, which could help form the next government. Right-wing lobbyists the Taxpayers’ Union, and some of Simpson’s colleagues, take market-fundamentalist lines. So it matters that these ideas are out there – and wrong.

That carbon prices should take the lead isn't some radical libertarian plot. Economists across the spectrum support letting prices lead. We polled NZ's top economists on it - and they span a range. They agreed. Just under 84% said that tightening the ETS cap is a less expensive way of cutting emissions than a collection of policies targeting emissions already covered by the ETS.

I wrote up the results for the Dom.

So either you can claim that the likes of Alan Bollard, Arthur Grimes, Gary Hawke, and Gail Pacheko are market-fundamentalists, which is obviously nonsense, or you're misleading your readers by insinuating that only 'market fundamentalists' take this position.

There are, for starters, changes that individuals and businesses simply cannot achieve. Only the government can make the investments in the national grid needed to enable more renewable energy.

Many price signals get lost in transmission.

If driving becomes costlier, but there are no decent walking, cycling or public-transport options, people won’t switch.

None of this is contrary to our position.

Well except the bit he gets just straight wrong.

The straight-wrong bit is that if by 'national grid' he means Transpower, that's an SOE that makes investments on a commercial basis facing regulated prices. If he means that plus the local lines companies, the latter have a big ownership mix but they make their own investment decisions and recoup costs using regulated fees on users. And if he takes the broadest view, to include generators, investment in generation is driven by commercial incentives. And that clean electricity market structure has resulted in a very high proportion of renewables - without subsidy.

But his bigger mistake is in setting up a chicken-and-egg argument against us. I have regularly argued that if some other real market failure comes in, then policies targeting that failure directly can make sense. And I have regularly argued that councils should be weighing rising carbon prices into their transport planning. There is no gotcha here, just misrepresentation.

Ditto if carbon pricing makes an EV cheaper over its lifetime, but families can’t afford the upfront cost. Hence the need for cycleways and clean-car discounts.

The market-fundamentalist view is also short-sighted.

There are lots of outfits that provide financing for cars. There's a whole industry association for the non-bank businesses that provide financing for cars, whether directly or through dealers. The only possible problem would hit those with really bad credit. But car loans are easier than personal loans - the lender can always repossess the thing. Plus there are lease options.

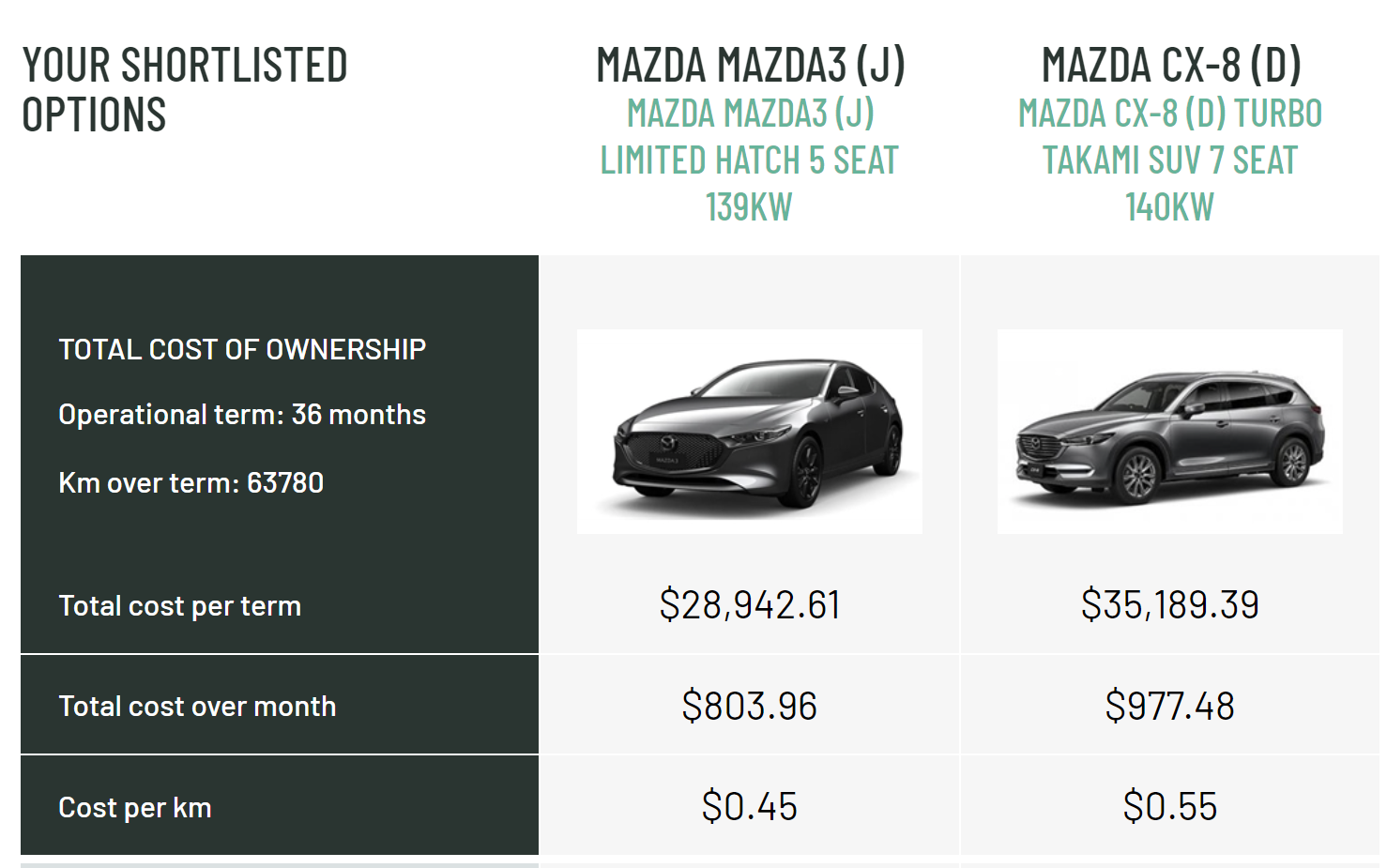

There is no market failure here. If the lifetime cost of the EV is lower, which it still isn't, then the sum of the monthly loan/lease payments plus running costs should be lower than the sum of the same for an internal combustion vehicle. And the time value of money isn't a market failure either.

Decades ago, solar and wind power were expensive, and shunned by market-fundamentalist politicians. Others, fortunately, understood that if government invests in something, its massive purchasing power can help create a market, allowing firms to rapidly drive down costs through learning-by-doing.

There's a potentially defensible argument that US and European subsidies drove some tech-forcing innovation. Is there any reasonable argument holding that the NZ govt has any kind of scale to bend that curve? No. The only spot where it starts being plausible is in ag biotech research, if NZ were to let other countries pick up the tech to use as well. That could plausibly bend global curves. Except that research is largely banned in NZ because of ongoing regulations around biotech.

Prices today are not the same as prices tomorrow. Those past state investments lie behind the now-plummeting price of wind and solar.

Another problem: since the carbon price increases gradually, it doesn’t always deter bad decisions now.

Firms invest in polluting technologies while they are still cheap; when the price rises, they must either abandon their stranded assets, or become powerful lobbyists for a high-pollution status quo.

There are carbon futures markets. You can check the prices, several years ahead, right now. A carbon credit for 2027 is currently trading at $93. Making an investment in something that will still be around and using carbon in 2027? You should be betting on a $93 carbon price in that year, and very likely continuing to rise thereafter.

Does Rashbrooke really think that Wellington bureaucrats can better plan investments for firms than they can themselves? Firms weigh this stuff up. They don't want to waste shareholder money.

You might as well claim, in the 1980s, "Oh, companies are all stupid because they haven't factored in peak oil and that they won't have any oil to buy in 2005 so we need a bureaucracy to make better decisions for them."

It's their own money that's at risk.

Part of the problem is that companies making very bottom-line based decisions on low-carbon tech then go on a greenwashing campaign, cloaking themselves in moral virtue about it, when really it was just way too expensive to keep using higher carbon tech. And then some people conclude that nobody is making investment in lower-carbon tech unless they're part of some enlightened few, and that regulation is needed for the rest.

Politically, too, emissions pricing alone is a losing strategy. The public feels the pain in higher prices, but sees no immediate gain. Politicians fare better if they can point to positive investments like improved public transport or job-rich green-energy schemes.

I agree with Rashbrooke here: the public feels the pain in higher prices, but sees no immediate gain. That is precisely why we have argued, ad nauseum, for a carbon dividend that rebates government ETS revenues back to households. Most households are then made better off by rising carbon prices. But Rashbrooke forgets that.

Such emission cuts might diminish the pressure on other parts of the economy to decarbonise – but if so, the government can simply reduce the number of carbon “permits” it issues to industry. It is plain wrong to say that policies beyond carbon pricing will achieve nothing.

It isn't the other policies that reduce net emissions, it's the reduction in the number of permits issued, whether as industrial allocations or at auction. The other policies are certainly not sufficient to reduce emissions; if you do it without cutting the cap, you only achieve a reallocation in where emissions happen. And they aren't necessary either: you can cut the cap without doing the other policies.

Policies beyond carbon pricing, targeting emissions in the covered sector, cannot do anything about net emissions unless coupled with a tighter cap - which could be done regardless of the policy.

Of course, as Burgess points out, one cheap way to meet our climate targets would be to forget about reducing the carbon we emit and simply plant more trees to suck it out of the atmosphere. But the required afforestation of another 1.5 million hectares of farmland would be politically untenable.

There is no guarantee the carbon would stay captured – what if the forests all burnt down, or were harvested with no replacement? Betting the farm on forestry, as it were, would be an unfathomable risk.

The ETS isn't that stupid.

If a forest burns down, the owner doesn't have to immediately surrender credits. Instead, the owner of a post-1989 burned forest receives no credits until the forest has regrown to match the carbon lost in the fire. That bit of burn-and-grow is net zero over that time horizon. Then it starts earning credits again.

If there's risk, it would be if a forest's owner declaring itself bankrupt after a fire AND the land could not be economically replanted even if the land value were zero on sale after bankruptcy (the new owner would have to regrow the forest before any new credits could be earned, or presumably face surrender obligations). IF that's a risk, government could require insurance against that risk or bonding.

Now that could still mean problems in whether emissions fall within particular five-year budgets, but so much the worse for the reliance on five-year budgets. Better to update the legislation to be consistent with a well-working ETS than to break the ETS to fit the legislation.

I don't get why people throw their hands up and say we have to abandon the ETS because of problems that have obvious solutions.

Rashbrooke suggests that increasing levels of forestry might hit political walls. We don't disagree. I've argued that this really is a local land-use planning issue rather than an issue for the ETS though. If a local council wants to put restrictions against forestry conversions in response to local pressure, and ideally with compensation for the affected owners, that's where that kind of action should be happening.

And the beautiful thing with an ETS is it just automatically re-routes. Suppose that local councils started talking about putting in these kinds of restrictions. The futures price in the ETS should start rising in response, then rise more once the restrictions come in. Higher ETS prices then mean that gross emission reductions that previously weren't cost-effective become cost-effective, and maybe new sequestration techniques come in. The pathway really doesn't matter. The cap on net emissions still binds, emission reductions still happen.

Forcing things through higher-cost channels does make it more urgent that we get a carbon dividend though.

And without wider action on issues like transport, New Zealanders risk becoming stranded, left trying to drive petrol cars in a world that no longer exports either petrol or cars.

I don't know why government is better placed than individuals to weigh up the risk that petrol or diesel will cease to be a thing within the lifetime of a purchased automobile. I expect individuals to weigh that risk up sensibly, knowing they bear the downside cost of getting it wrong. It isn't that individuals are perfect at guessing this stuff, it's more that government has no particular advantage in it - unless they're trading on insider knowledge of that they will ban petrol or diesel rather than just let the ETS work.

Of course prices can be a useful tool. But there is so much they can’t comprehend.

Encouraging cycling, for instance, cuts emissions – but also makes for happier and healthier people. Only by looking beyond carbon prices will we spy such opportunities.

This isn’t just a crisis: it’s also a chance, as Simpson puts it, to create “behavioural change in the way we live, do business, and exist as a society”.

It requires us to make collective decisions on collective investments – and not just force the choices onto isolated individuals grappling with a crude price instrument.

The point of net zero isn't inducing behavioural change in the way we live, do business, and exist as a society. The point of net zero is reducing carbon emissions to a net of zero, so we don't heat the planet by more than is already baked in.

If there are other benefits from other things, like cycling, weigh that up on its own basis. If a council's residents want more cycleways, whether because of expected rising carbon costs, or just because they like cycling, and they judge the cost to be worthwhile, then councils should invest in cycleways. But selling things like cycleways on the basis of emission reductions, when emission reductions are only driven by reductions in the cap, isn't right.

I have a bit of trouble steelmanning the kind of argument that Rashbrooke, and a lot of others, make. It just seems inconsistent with the basic maths of the ETS. The best version I've been able to come up with thus far is this:

The ETS is well and good but it requires that successive governments continue to be willing to tighten the cap to get us to Net Zero. There are political risks along the way, including changes in voter preferences.

Regulatory mandates might be a lot less cost-effective than the ETS, but they lock in a path that is harder to break. If we mandate, today, that companies and households take on a pile of investments that can only make sense in a $500/tonne carbon world, even though the current ETS price is less than a fifth of that, those become their own stranded assets and sunk costs. If a future government changes things, at least we've locked in a quantum of reductions for a while - even those those could be undone with further investments.

It is easier for a future government to renege on reductions in the cap than it is for a future government to undo the effects of regulatory edicts, even if those edicts are only in place for a few years.

I've never seen them put it this way; I don't know if this is what is underlying their thinking. It's the only consistent rationale for the underlying argument that I can understand that doesn't rely on impugning their motives. The alternative version is that they just want to force behavioural changes for aesthetic reasons, which seems a bit evil, and I at least try to come up with explanations that don't rely on the other side just being bad people.

If the version I've put up is the underlying fear, then I think there's a better solution. Set a cap on the quantity of permits that the government is prepared to issue between now and 2050. Do it through cross-party consensus. And set a requirement that the government compensate the holders of existing credits, or of credit-generating facilities like forests, if the government debases NZU by just printing more unbacked credits.

Oh - and I've not managed to come back to the link to international markets.

It's pretty simple.

Right now, when the ETS price hits a trigger value, the government first issues some additional NZU that are within the ETS budget, then it issues some units that have to be backed by reductions elsewhere - potentially even from offshore.

Re-jig this.

Instead of having the price cap anchored in some nominal amount, have it track the volume-weighted carbon price in the set of ETS markets abroad that the Climate Commission declares to be credible.

That price cap will be higher than the price here because it will be pulled by Europe.

At the price cap, the government would immediately back units by buying and retiring units in the cheapest market from the set of markets whose weighted average prices define the cap. The government need set no quantity restriction on this - the units are backed by reductions in emissions in those other markets. The price cap would be more politically credible because the government would make money at the cap rather than bearing risk - remember, the cap is a weighted average of prices, but the government would buy in the cheapest of the credible markets.

There isn't a right price for carbon, but there can be a lot of wrong ones. If the carbon price in NZ, as the ETS cap tightens, winds up being higher than prices in Europe, that means we could do more to reduce net emissions by buying and shredding credits there, rather than doing more stuff here. If we care about doing the most we can to reduce net emissions, then a price above the going price elsewhere is a wrong price.