Here's some stats background before we look at Oxfam.

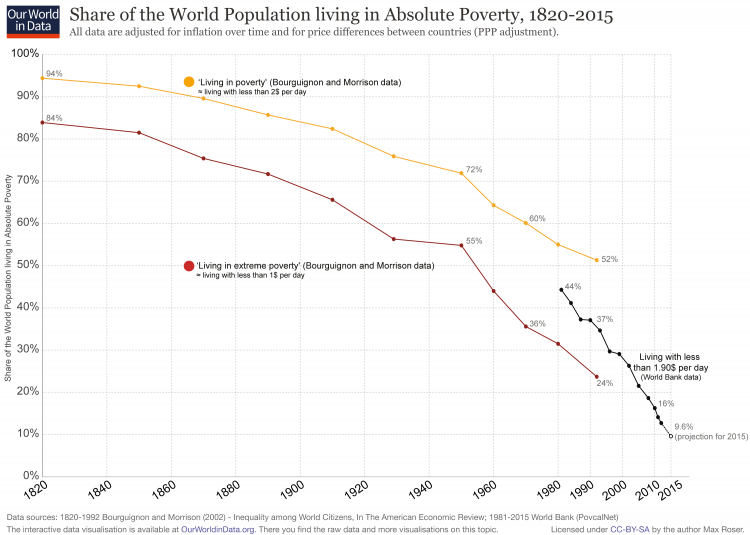

Below is Max Roser's chart on global poverty. The decline over the past two decades has been staggering.

Meanwhile, here in New Zealand, income inequality has been stagnant over the past two decades; consumption inequality is lower than it was in 1984; and, wealth inequality is on par with OECD averages. Here's the table on wealth inequality from our recent report on inequality.

Anyway, over to Oxfam:

The numbers they're reporting as shocking aren't really much different from the last couple sets of numbers on wealth inequality that Statistics New Zealand has put out. You shouldn't be shocked by these figures unless you really haven't looked at them before.According to the Oxfam research, the richest 1 per cent of Kiwis have 20 per cent of the wealth in New Zealand, with 90 per cent of the population owning less than half of the country's wealth.

Rachael Le Mesurier, executive director of Oxfam NZ, said the organisation was shocked to discover such a level of wealth inequality."The gap between the extremely wealthy and the rest of us is greater than we thought, both in New Zealand and around the world. It is trapping huge numbers of people in poverty and fracturing our societies - as seen in New Zealand in the changing profile of home ownership."

But, Oxfam is right that there are serious problems in New Zealand's housing markets.

The Herald's Nick Jones asked me for comment; he quotes me well in his article. I've copied below the full bit I emailed him; there was never going to be room for all of it in the published piece.

The share of the world population living in absolute poverty Is lower than it has ever been. Work by Max Roser at Oxford shows just how dramatic the drop in poverty has been. More than half of everyone in the world lived in extreme poverty in 1960, defined as living with less than $1 per day, inflation-adjusted. It was worse before then. By 2015, less than 10% of the world lived on less than $1.90 per day. Roser's figures similarly show substantial decline in global income inequality over the same period; it's projected to drop even further through 2035. Longer term data series on wealth shares are harder to come by, but work by Tony Atkinson and coauthors earlier this year showed that the top 1% in the UK held 70% of UK wealth in the late 1800s and early 1900s; that declined to about 15% of UK wealth by the early 1990s and even today is around 20%. The big story of the past century is the global diffusion of wealth and income, and a massive decline in poverty.Me in the NBR on last year's iteration of this thing...

And so Oxfam's focus on wealth inequality is strange. It is entirely appropriate to look closely at wealth inequality in countries where tinpot rulers immiserate their citizens for the benefit of themselves and their ruling cliques. In those places, political regimes focused on extracting the country's wealth for the ruling elite simultaneously cause high inequality and very poor conditions for everyone else, and low rates of economic growth. But elsewhere, people become wealthy by producing goods and services that others value. Bill Gates becoming a dollar richer immiserates no one.While I have not seen this year's Oxfam report, just over 450,000 Kiwis counted as being in the world's wealthiest one percent in last year's figures. Owning a house in Auckland mortgage-free was just about enough to guarantee membership in the global top 1%. Oxfam tells us nothing new in 'revealing' that NZ's top 1% own about 20% of all wealth; similar figures were released by Statistics New Zealand last year - and also showed that New Zealand's wealth concentration is pretty middling in OECD rankings. The New Zealand Initiative's report on inequality last year also covered these statistics. One should also be cautious about figures assessing the wealth share held by the bottom fraction of the population in countries like New Zealand, where a lot of graduates' student debt will count against them while their degrees do not count in their favour. If we took these kinds of statistics too seriously, a new doctor graduating with a $100,000 student loan would count as poorer than families experiencing real hardship but who have less net debt.

Inequality's real bite in New Zealand, as our recent report shows, comes through effects in broken housing markets. Inequality in access to affordable, quality housing, because zoning rules prevent its being built, is an incredibly serious issue.

No comments:

Post a Comment