I had to trim last week's NBR column to fit the page. Here's the original. Enjoy!

New Zealand’s climate change policy could stand to be just a little more vanilla.I particularly recommend adding coffee to the Vanilla Bean as an affogato.

When Cyclone Enawo hit Africa’s east coast in 2017, it wiped out about 16% of the world’s vanilla production. The cyclone came on the back of droughts that hurt the 2016 crop; there was no huge buffer to meet demand.

So, globally, vanilla users had to cut back their consumption by about a sixth – and in a hurry. Of course, unless you were directly involved in the vanilla industry, or were a baker using vanilla in weekend pancakes, you probably did not even notice.

There were no Ministers in Charge of Vanilla Change sending out a dozen press releases a week proving they were taking the problem seriously. There were no Vanilla Commissions or Taskforces. No Productivity Commission reports on the best ways for New Zealand to respond to its shared vanilla crisis. No MBIE advice on preferred ways of subsidising alternatives to vanilla in ice cream.

Bernard Hickey didn’t even show up to propose special taxes on “Vanilla-guzzling” concoctions from Wellington ice cream and gelato institution Kaffee Eis, with all taxes collected helping subsidise vanilla for the Girl Guides in hope of bringing back their soon-to-be-cancelled vanilla-flavoured biscuits.

Instead of all that ruckus, markets simply worked their regular vanilla-flavoured magic. Prices worked.

Economist Alex Tabarrok says prices are a signal wrapped in an incentive. The spiking price of vanilla signalled relative scarcity, along with an incentive for everyone to change their behaviour. Those most readily able to reduce their use of vanilla would be the first to adapt. Vanilla by-products started being pressed into service – spent vanilla flecks almost quadrupled in price, according to the Financial Times.

And those for whom vanilla was most critical, as they judged for themselves and demonstrated with their own money, simply lumped the price increase.

It is exceptionally difficult to come up with policy options that beat simply letting prices work.

Every alternative I have suggested around grand government vanilla strategies would have been worse. If the government was exceptionally lucky, it would have required firms here to do what they had already figured out would be best for them in their own particular circumstances. But in every other case, the government would have enforced unnecessarily costly adjustments. No Minister or Ministry can tell what the best substitutes are for different users, or which uses are most valuable to whom. That kind of knowledge can only emerge from the interplay of buyers and sellers in markets, and is otherwise invisible to Wellington desk-jockeys.

The New Zealand government has committed to reducing our greenhouse gas emissions. Fortunately, New Zealand has a functioning Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). Every litre of petrol or diesel you purchase includes the cost of the New Zealand Units (NZU) purchased in the ETS to cover the fuel’s eventual carbon dioxide emissions. Electricity is in the ETS, so every kilowatt of power put into the system by coal, gas or geothermal generators requires those generators to purchase carbon credits. And the government has also committed to strengthening the ETS.

If there were no way of pricing carbon dioxide emissions, the government would be forced into a lot of rather second- or third-best alternatives. The government would have to guess how different industries, firms and consumers would behave in a world with carbon prices and then set regulations, taxes and subsidies to encourage those behaviours. It would be dreadfully inefficient compared to what prices can achieve through the direction of no one, but there would be some interventions that would still likely be worthwhile.

When we do have a functioning ETS, though, layering additional subsidies and regulations on top of the scheme, and particularly for those sectors already covered by the ETS, very easily risks New Zealand failing to do nearly as much as it could to reduce emissions.

The best that a government committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions can do is to make sure the ETS is working as well as possible, then buy back and retire credits in the system. Those able to most easily reduce their own carbon emissions will be the first to sell; those for whom change is difficult will be last to sell – exactly how people responded to vanilla price increases. No Minister or Ministry has to guess who can most easily adapt.

Buying back credits within the ETS, rather than forcing particular sectors to change through regulation or bans, helps make sure New Zealand gets the greatest emission reductions per dollar’s worth of effort put to the cause.

Regulatory options, like mandatory fuel economy standards, or electric vehicle subsidies, risk doing harm because of the good forgone. An electric vehicle subsidy is unlikely to increase greenhouse gas emissions. But it would increase emissions compared to putting the same amount of money towards buying up and retiring credits in the ETS.

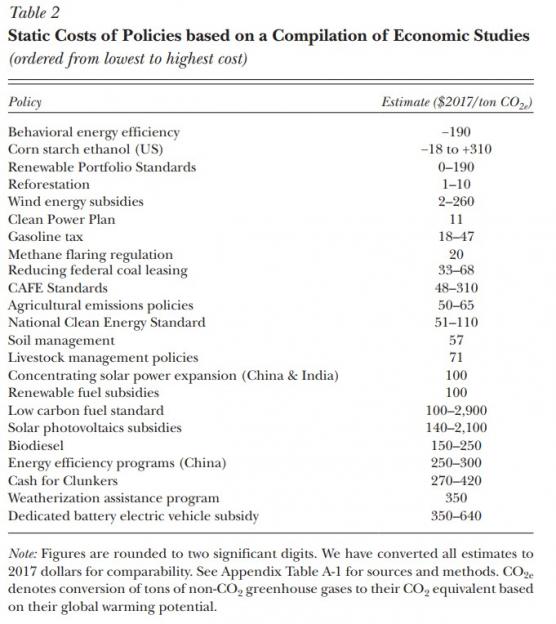

Different policies have very different costs per tonne of carbon dioxide mitigated. A government using regulatory alternatives has to pray it has modelled those costs correctly and found the carbon best-buys.

Work published in the fall issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives summarises recent estimates of the static costs of policies mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards in the United States cost between US$48 and $310 per ton of carbon dioxide mitigated. But NZU is selling on the spot market for around NZ$25. Imposing similar rules here would then be, at best, about a third as effective in reducing emissions than simply expending the same resources on buying and retiring NZU.

Kenneth Gillingham and James Stock. 2018. "The Cost of Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions" Journal of Economic Perspectives 32:4 (Fall).

The journal article does note that dynamic effects can vary: If there were no electric vehicle charging stations, a chicken-and-egg problem could prevent people from taking up electric vehicles if those make sense for them, so policy could help. And if a government as large as America’s starts subsidising buying huge volumes of solar panels, it could encourage technological innovation that reduces costs across the board.

But neither case seems particularly relevant: There are few major transport routes without charging stations now, and New Zealand demand for batteries or solar panels is not likely to be large enough to drive broader technological change. And while New Zealand could plausibly lead change through biotechnology advances in better low-emissions pastoral systems, if the grasses cutting greenhouse gas emissions were developed using genetic engineering, the government already bans their use.

It is also rather likely that successful dynamic investments of this sort are easier to identify in hindsight than with foresight. Buying back ETS credits yields more certain returns.

New Zealand’s climate change policy could stand to be a lot more vanilla. Simply making sure the market is working well, strengthening it where needed, and then buying back credits might sound boring. But vanilla really can be excellent. If you don’t believe me, try the Vanilla Bean at Kaffee Eis.

No comments:

Post a Comment