Susan Edmunds at Stuff asked me what effect Labour's proposed new tax rate on earnings above $180k might have on the usual "people in the top x% pay y% of all income tax" figures.

The actual answer is complicated. Some on those kinds of incomes can just reduce their wage income and keep income within a company structure, where it would hit a lower tax rate until earnings might be dispersed.

But Labour had had estimates of that the new tax rate would earn $550m per year from the top 2% of earners. If we take the total income tax paid by those on >$150k per year, add the $550m from those above $180k, you can ballpark it.

Using 2019 figures, the top 3% of earners on $150k+ paid 23.5% of all income tax. Adding the expected revenues from the new tax rate would increase that to 24.7%.

I don't think that's any material difference.

So my notes back to Susan included this bit that she used:

“Income tax is only one part of the Government’s overall tax take, though. GST, company tax and excise all also matter. Focusing on income tax alone would then overstate the proportion of overall revenues paid by the highest-earners.

“On the other hand, the Government provides many income transfers, some of which are targeted by income, some of which are universal.”

He said data from 2010 showed the bottom 40 per cent of households each received about $20,000 more in services than they paid in taxes, while the top 10 per cent of households paid about $50,000 more in tax than they received in services and transfers.

Crampton said lower-income people had been more heavily affected by Covid-19 job losses, which could skew the tax bill even further to higher incomes.

But he said some higher earners would also restructure their affairs to make the most of lower company and trust tax rates, to reduce their overall tax bills when facing a new, higher rate. Most companies are taxed at a flat rate of 28 per cent.

It would be great to get an update of those 2010 Policy Quarterly figures; it would be a big job to do it though.

For my sins in being helpful when a reporter called asking for an update on a commonly-used figure:

(The story the NZ Initiative is trying to put around is here: https://t.co/VtXU8xkBco. As Zucman points out claims like this partly just highlight how unequal NZ is, and how much is earned by the top 3%. It’s no reason for alarm.) /2

— Max Harris (@MaxHarr03421445) November 5, 2020

I think it's pretty funny. Running a simple calc when a journalist calls asking for an update on a basic number, well, if that's raising an alarm, I'm not quite sure how I'd characterize my more normal ways of raising alarms.

When I'm trying to raise some kind of alarm about something, it isn't that hard to tell. I'll be jumping up and down about it on Twitter, putting out press releases, and writing reports or short policy notes.

I'd not bothered running the calculation before because I'd never seen it as being all that important.

I had seen misperceptions of the effects of the Greens' proposed wealth tax as being important.

My raising the alarm about stuff tends more to look like this:

The Greens' proposed wealth tax would catch WAY more than 6% of Kiwis.

Newstalk:— Eric Crampton (@EricCrampton) October 12, 2020

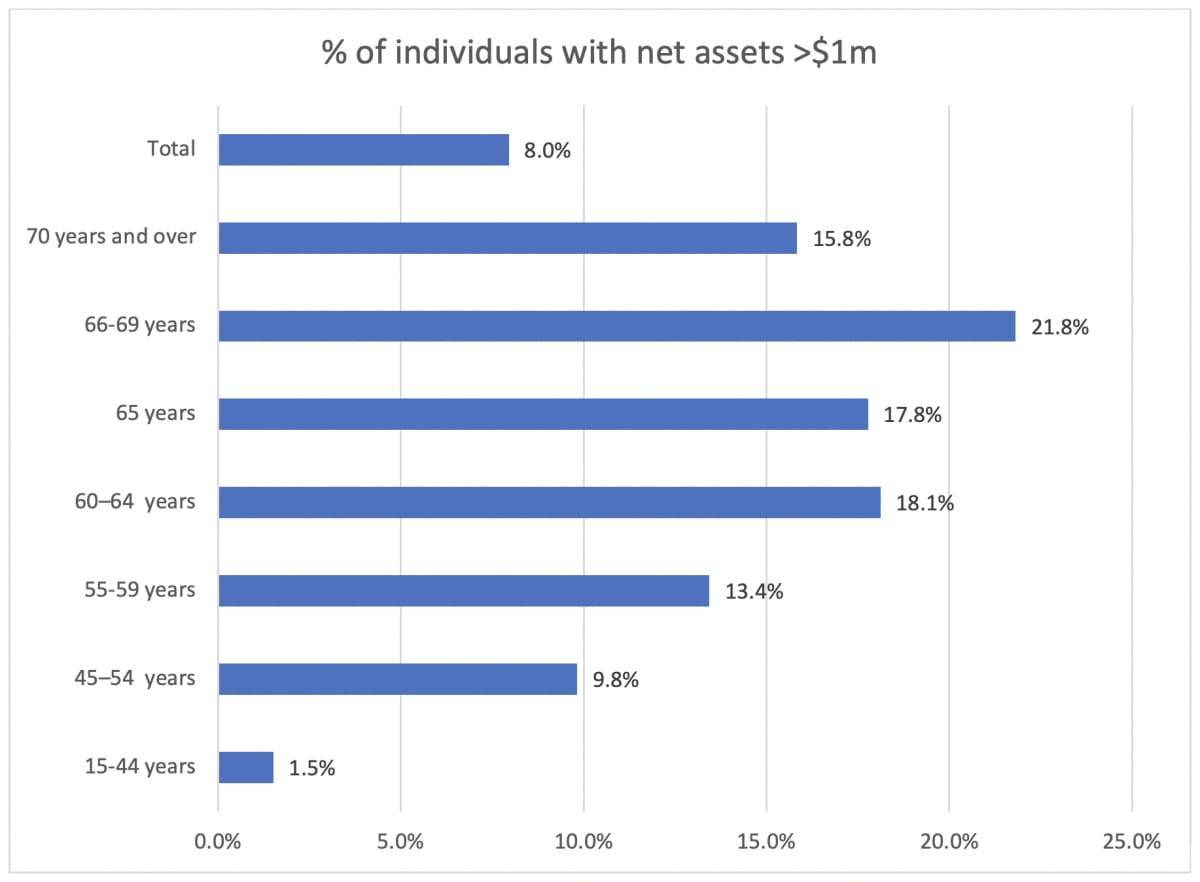

Over 20% aged 66-69 have over $1m in net wealth. Somewhere between a fifth and a quarter of Kiwis should expect to be liable, if the thresholds adjust with inflation.https://t.co/1Il8W3xxuV pic.twitter.com/3tJIcELQPf

One economist claims the Greens' wealth tax will hit more Kiwis than the Party thinks.Newsroom

The Greens say the tax, which has become a hot issue in the final week of the election, would only affect the top six per cent of the population.

However, New Zealand Initiative economist Eric Crampton told Heather du Plessis-Allan the real number's closer to 20 per cent.

He says right now, about 20 per cent of retirees would be subject to it.

And he expects future generations will also build wealth over their lifetime, reaching a peak after retirement.

"We need to be thinking not just about who is currently subject to the wealth tax, but who can we expect to be subject to the wealth tax."

But the Greens’ numbers have their own problems. To go through those, we need a brief detour through basic wealth dynamics. It is a problem plaguing every iteration of wealth inequality surveys using static comparisons to make claims about what proportion of wealth is held by which proportion of people.

Wealth builds over time, and that matters for every question about wealth measurement.

Most people start life with little wealth. Taking on student loans to earn a higher income later on means beginning adulthood with a heavy net debt position, as education does not contribute to measured wealth on Statistics New Zealand’s balance sheets. As graduates move into employment, they begin paying down their student loan debt while (hopefully) building up savings. If they buy a house, they take on debt that has an offsetting and appreciating asset. Otherwise, they build up retirement savings.

Individual net wealth peaks shortly after retirement. Retirees then draw on those savings.

A cross-sectional snapshot of the country will reveal a lot of people with net debt, a lot of people with few net assets, and a few people with a lot of net assets. That, and the failure to account for the effects of New Zealand Superannuation, can make wealth distributions look more unequal than they really are.

Even if every Kiwi followed exactly the same wealth trajectory, beginning with net debt and ending with the same retirement net worth, simple differences in ages would mean that a small proportion would be wealthy at any given time.

The Greens argue that only 6 percent of Kiwis would be subject to their wealth tax. But that seemed almost certainly to be based on a misleading cross-sectional snapshot. A reasonable proportion of today’s youth would be subject to the tax as they reach retirement. After prodding their representatives on Twitter more than a few times if they had checked what proportion of retirees might be subject to the tax, I decided to ask Statistics New Zealand instead.

I asked Stats to go back through the 2018 Net Worth Survey and sort net wealth holdings by age.

Without any sorting by age, the 2018 survey suggested 8 percent of individuals held net wealth in excess of $1m – so that was already rather higher than the 6 percent suggested by the Greens.

And, as expected, there was a severe age skew in the data. While only 1.5 percent of those aged 15-44 held a $1m in net assets, that proportion rose steadily for older age groups. Just over 18 percent of those aged 60-64 reported more than $1m in net assets, along with just under 18 percent of 65-year-olds. Wealth peaks among those aged 66-69 which means 21.8 percent of retirees would be liable for the wealth tax.

I'm not exactly subtle when I'm actually raising an alarm about something. I tend to get a bit excited and go on about it.

No comments:

Post a Comment