Before we start working through Otago's latest missive on minimum alcohol pricing, let's re-state a few baseline facts.

- Heavy drinkers are less price responsive than are moderate drinkers. This is well established in Wagenaar's metastudy, and is recognized (but then later ignored) in the Ministry of Justice's report on alcohol minimum pricing. Here's a table from that MoJ report. Heavy drinkers are somewhere around half as responsive to price increases as are moderate drinkers.

- Heavy alcohol use substantially increases your risk of some disorders: these disorders have positive aetiological fractions in normal tables looking at alcohol's burden on the health system. But alcohol use also reduces the incidence of other disorders: these then typically get negative aetiological fractions. The 2008 Collins & Lapsley report in Australia included both the positive and negative health effects. When you add up all of the positive and negative effects, you get reduced all-source mortality risk, as compared to non-drinkers, up through consumption of about four standard drinks per day, with risk minimised at a bit under a standard drink per day. I summarised the evidence on the alcohol J-curve here and here, and contrasted it with the New Zealand Ministry of Health's view here. Prior concerns about mixing former drinkers with never drinkers were worth worrying about, but have long since been answered.

Here are the key graphs from DiCastelnuovo and Donati:

You can also check effects on morbidity in the Nurses's Cohort Study, which showed that alcohol consumption in middle age predicts better outcomes in old age.

- Drinkers get consumption benefits from drinking. You don't have to assume perfect rationality to recognise that alcohol consumption is pleasurable for many many people. You can build stories around how imperfect information or bounded rationality could yield too much consumption for an individual relative to how that individual would judge things in a perfect world, but that just says that there is some net excess costs from the last units of consumption, not that all the prior units were worthless. The Ministry of Justice report handled this well by counting consumption reduction under minimum pricing or increased excise as a harm imposed on those consumers that could be offset by some health or other benefits.

Blakely, Connor and Wilson start by citing a

recent Lancet paper by Holmes et al [sorry, that's a ScienceDirect subscription link] in support of alcohol minimum pricing that found the largest effects on lower-income harmful drinkers. And, sure enough, the Lancet paper does claim that minimum pricing's largest effects would be on harmful drinkers. But how do they get there? For that, we need turn to the

supplementary tables.*** And things there just seem a bit odd. Let's go through it.

First, their estimates of health effects are based on aetiological tables (See Tables A3 and A4, and adjusted tables A14-A17) that assume positive aetiological fractions on heart failure, cholelithiasis, ischaemic heart disease, and hypertensive diseases.

Here's Collins and Lapsley, 2008, on those disorders:

Collins & Lapsley note that you can get no negative aetiological fractions if you follow English et al, 1995, in looking at the increment of drinking above the safe level of drinking; this would be appropriate for interventions that have no effect on light and moderate drinkers and only affect heavy drinkers. That won't be the case for pricing measures. So the Lancet's health effects have a heavy thumb on the scale: they assume no health costs to moderate and light drinkers when their consumption drops with minimum pricing.

Perhaps this doesn't matter as much in the Holmes et al paper if we buy their second big assumption: that the price elasticity of alcohol demand is very different from our best consensus estimates.**** They argue that alcohol consumption is pretty elastic while using estimates that have heavy drinkers just as price responsive as moderate drinkers. As a robustness check, they test the case where heavy drinkers are much more responsive to prices than are light drinkers - the opposite of the evidence I've cited above. A proper robustness check would be based on Wagenaar or Gallet's estimates.

Holmes et al's Table 1 (main paper) provides the elasticity estimates they get from the UK Living Costs and Food Survey (LCF). I've copied that below:

The diagonal has the own-price elasticities for each beverage category; the off-diagonals have the cross-price elasticity. The column shows the effect on a particular beverage's consumption of a one percent increase in the price of the beverage listed in the row. So, if we were to increase the price of each beverage category by 1%, we could sum up the effects down each column to get the total effect on each beverage.

When you do that, you find that a 1% across-the-board price increase yields:

- a 0.94% (1.12%) reduction in off-trade (on-trade) beer purchases,

- a 1.14% (0.07%) reduction in off-trade (on-trade) cider purchases,

- a 0.12% reduction (0.76% increase) in off-trade (on-trade) wine purchases,

- a 0.5% reduction (0.07% increase) in off-trade (on-trade) spirits purchases, and

- a 0.62% reduction (1.13% increase) off-trade (on-trade) RTD purchases.

None of that seems particularly plausible. Elastic cross-price elasticities can be plausible where consumers shift to other products. But if you were to put a 10% ad valorem tariff on all products containing alcohol on top of existing prices, I sure wouldn't expect about a 10% reduction in beer purchases. I'd expect about a 4% reduction. And while I can imagine that minimum prices could yield a shift from off-licence to on-licence consumption, the table isn't giving the effects of a minimum price, it's giving the effect of a one-percent increase in each category's price.

When SHORE provided the Ministry of Justice with elasticity estimates that were more than unit elastic, the

MoJ report noted (p. 25):

Another significant concern is that the size of the elasticity estimates generated by AC Nielsen and the SHORE and Whariki Research Centre are very large compared to international estimates, and result in significant changes in consumption when the various pricing options are analysed. The large off-licence elasticities may be driven by the fact that both regular prices and promotional prices are included in the elasticities. The large on-licence elasticities are likely to be a consequence of a reasonably small sample size and cross-sectional data.

It looks like the LCF suffers from the same problem that the NZ MoJ noted: they're deriving elasticities from consumer reports of weekly purchases and weekly prices paid where there's pretty substantial chance that consumers buy a lot when goods are on special to stock up for weeks in which goods are not on special. Elasticity estimates out of this kind of approach would be useful for a brewer deciding whether to put some stock on special, but perhaps less useful in figuring out the effects of blanket price increases that persist.

If you tracked my purchasing behaviour, you'd say I'm really very price sensitive. When somebody had the 2008 Penfolds Bin 28 on special a few years ago, I bought several bottles. When it's north of $30 a bottle, I don't touch it. I've only just opened that case. Consumption smooths over time; purchases are lumpy. I'll do the same thing with beer: when a great beer is on special, I buy a lot of it; when it's not, I might buy only a bottle. My day-to-day consumption doesn't vary, but my inventory changes. I do this because I'm cheap, I have a low(ish) discount rate, and I like keeping a reasonable stock of alcohol in case of emergency. If heavy drinkers pay more attention to what's on special than I do, then we might expect that their elasticity estimates are particularly unsound.

So, the study assumes that heavy drinkers are just as responsive to prices as are moderate drinkers, and that both are reasonably price-elastic. Because heavy drinkers spend a lot more of their money on alcohol, and because they're purchasing more of the lower-cost products, minimum prices have a larger effect on them. And, because they've assumed that moderate drinking has no health benefits, there's no offsetting health losses for those moderate drinkers that do reduce their consumption. If instead heavy drinkers are more likely to be watching for what's on special and are otherwise less price responsive than are moderate drinkers then we might worry about some of the conclusions in this study.

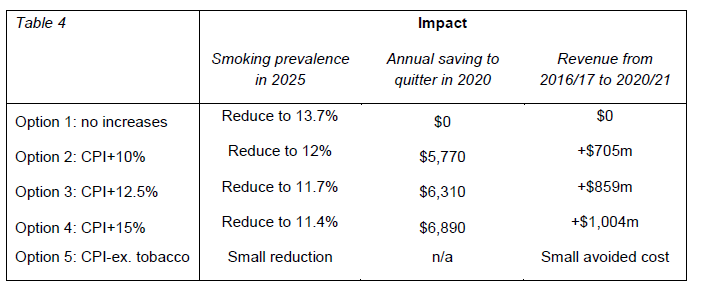

The discussion about whether minimum unit pricing is likely to be effective policy for New Zealand depends on the outcomes that are considered. The government’s analysis is focused only on whether the policy will deliver reductions in alcohol consumption by the heaviest drinkers, without increasing the cost of the cheapest alcohol to those who don’t drink so much. This is to misunderstand the range of benefits that can be attained by reducing alcohol consumption in all drinkers, and to undervalue the reduction in adverse effects of other people’s heavy drinking.

The gains come from putting a minimum price of alcohol that prices the poor out from consumption. Consumption that has a benefit – something that is ignored constantly.

Talk about evidence all you want (a lot hopefully – as evidence is central, and I respect the PHB for bringing empirical research up so constantly), but if your ethical framework places zero benefit on consumption choices of the poor your policy conclusion will be restricting the choice of those in poverty – always.

Nolan's right about the main problem here. But the empirical case they're making isn't nearly as sound as they're letting on. Heavy drinkers are far less price responsive than are moderate drinkers, as noted above and in the MoJ study.

Binge drinkers also aren't all that price-responsive.

Connor et al write:

Concern over the effects of policy on drinkers other than those with the most harmful patterns is only warranted if reduction in consumption in these groups and the consequent health benefits are considered a poor outcome. Many harmful effects of alcohol have no threshold. For example, the leading cause of alcohol-related death in NZ women is breast cancer, and a woman who drinks two small glasses of wine a day has a 10% higher risk of breast cancer than a woman who has one. There are also substantial secondary benefits from reduction in other people’s drinking in the community – all for the price of giving up very cheap alcohol. These benefits include reduction in the risk that you or someone close to you will be injured by a drinker, the reduction in vandalism, disorder and intimidation in neighbourhoods and urban centres, and the large economic benefits to the country through reduction in healthcare costs and responses to crime.

The MoJ report at least started with the right framework: we should treat it as a cost to drinkers that they be curtailed from drinking, and we should treat it as a benefit to others if drunks then do them less harm. Because their elasticity estimates were out of whack, they overestimated the benefits that could be obtained per unit pain imposed on moderate drinkers. But the framework made sense. Connor et al above say we shouldn't even be thinking about the effects of policies on consumption enjoyment among moderate drinkers. And even if we were restricting things to health benefits, it's odd to restrict our consideration to those health effects that are negative. It's total mortality and morbidity that should matter for population health. And we might also worry that the evidence on light drinking and cancer may be confounded by consumption under-reporting.

Here's Klatsky et al:

Abstract

PURPOSE:

There is compelling evidence that heavy alcohol drinking is related to increased risk of several cancer types, but the relationship of light-moderate drinking is less clear. We explored the role of inferred underreporting among light-moderate drinkers on the association between alcoholintake and cancer risk.

METHODS:

In a cohort of 127,176 persons, we studied risk of any cancer, a composite of five alcohol-associated cancer types, and female breast cancer. Alcohol intake was reported at baseline health examinations, and 14,880 persons were subsequently diagnosed with cancer. Cox proportional hazard models were controlled for seven covariates. Based on other computer-stored information about alcohol habits, we stratified subjects into 18.4 % (23,363) suspected of underreporting, 46.5 % (59,173) not suspected of underreporting, and 35.1 % (44,640) of unsure underreporting status.

RESULTS:

Persons reporting light-moderate drinking had increased cancer risk in this cohort. For example, the hazard ratios (95 % confidence intervals) for risk of any cancer were 1.10 (1.04-1.17) at <1 drink per day and 1.15 (1.08-1.23) at 1-2 drinks per day. Increased risk of cancer was concentrated in the stratum suspected of underreporting. For example, among persons reporting 1-2 drinks per day risk of any cancer was 1.33 (1.21-1.45) among those suspected of underreporting, 0.98 (0.87-1.09) among those not suspected, and 1.20 (1.10-1.31) among those of unsure status. These disparities were similar for the alcohol-related composite and for breast cancer.

CONCLUSIONS:

We conclude that the apparent increased risk of cancer among light-moderate drinkers may be substantially due to underreporting of intake.

Connor et al,

as usual, insinuate that moneyed interests prevented their preferred lovely policy's adoption.

It is difficult to understand the government’s decision when the Ministry of Justice report appears to appreciate the evidence-base for minimum unit pricing. Also the evidence from Sheffield and British Columbia have been available for some time. When the British government reneged on its commitment to introduce this policy in July last year, Prof Sir Ian Gilmore, chairman of the Alcohol Health Alliance UK, said the government had “caved in to lobbying from big business and reneged on its commitment to tackle alcohol sold at pocket-money prices“.

There's a better and simpler explanation: the evidence base in the MoJ report was weak given their elasticity estimates, and the government wasn't keen on running a nanny-state initiative in an election year unless the evidence were stronger.

So, some bottom lines:

- The elasticities reported in the Lancet study are out of line with what we'd typically expect;

- The health benefits reported in the Lancet study are very likely widely overestimated due to overestimation of heavy drinkers' price responsiveness and due to the Lancet paper's ignoring of the health benefits of moderate consumption (and the forgoing of same when price hikes induce moderate drinkers to cut back);

- The NZ Ministry of Justice report itself noted substantial problems in their elasticity estimates; the Minister was consequently entirely right to shelve plans for substantial price hikes or minimum pricing;

-

See also Bill Kaye-Blake on this one. He commented:

The report appears to be a masterwork of consulting. It freely acknowledges that parameters are wrong and then uses them anyway. I’ve never had the guts to do that.

There is a reasonable case for minimum alcohol pricing when combined with lower overall excise:

if there's reasonable evidence that lower-priced products are disproportionately consumed by harmful consumers

and that we consequently do more to abate harms in that cohort than we do to impose harms on poorer moderate consumers, then minimum pricing lets you increase prices at the bottom end without doing as much harm to moderate consumption among middle-income consumers. But it has to be an empirical case based on reasonable elasticity estimates and weighing appropriately both harm reduction

and consumption losses. The MoJ report failed on the elasticity estimates but at least got the framework right; the Connor et al post didn't seem to think the consumption losses mattered.

Previously:

Disclosures:

as I will be ceasing employment with the University of Canterbury effective 14 July, the Brewers' Association of Australia and New Zealand has ended its contract with the University;

my prior disclosures statement no longer applies. I am doing a bit of expert witness work on local alcohol policies that has nothing to do with minimum pricing.

* I totally don't understand why the University of Otago lets them put its logo on their blog. I'd never put the Canterbury one on mine because I'd never want it to be seen as being some official view of the Department or University, and I expect that Canterbury's branding poo-bahs would have disallowed it if I'd have asked. This is one of the happy instances where the University likely would have barred me from something that I really never wanted to do anyway.

** Lame excuses are lame. But it did suck away more time than expected.

*** I could only get the link to the supplemental materials to show up when I opened it in IE rather than Chrome. Good luck.

**** But, at 1.1.3 in the appendix, they say that they're evaluating mortality relative to a "everybody stops drinking" scenario. In that case, the J-curve is going to matter a lot.