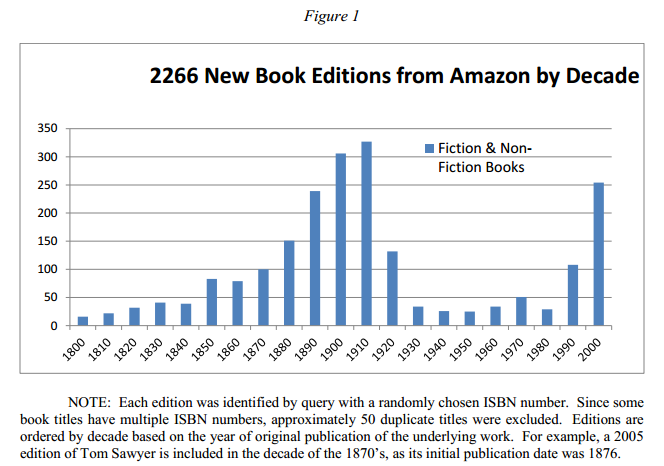

First, here's that "hump":

How could we tell how much value is lost from orphaned works from the 1930s and onward?

Smith et al, 2012, matched out-of-print books that do and do not have Kindle versions and estimate $740 million in revenue were all out-of-print editions to be available as e-books. I've a few doubts about that number.**

Heald provides other evidence consistent with a reasonable loss induced by the copyright wall. First, used book markets stock a much larger proportion of books first published in the 50s through 80s than does the Amazon sample that Heald previously examined. The blue line in the graph below shows the number of books listed at Abe Books by decade of publication; the red line puts the Amazon sample onto the same scale to illustrate some of the proportionate differences.

But Heald's most compelling evidence comes from NYTimes and library data.

He reports that 94% of the 165 best-sellers of the 1913-1922 era are currently available as eBooks and 98% are currently in print. But, only 27% of the 167 best-sellers of 1923-1932 are available as eBooks and 78% of that era's best-sellers are currently in print; only one of the copyright-walled best-sellers that has fallen out-of-print is available as an eBook.

He also finds that a surprisingly small proportion of post 1930s NYTimes reviewed books, the set of books most likely to be of continuing relevance, are available in digital form. Popular books prior to the copyright wall are more commonly available. And, older music is even more commonly available:

The barrier for accessing out-of-print, but formerly popular, books is substantial. Chicago library data suggests only 55% of out-of-print NYT Reviewed books are available at the library, with older books especially hard to find.

Older music seems less affected by the copyright wall, likely because it's generally simpler to produce a digital copy of a recorded work than of a print work. Heald explains that rights issues can be more complicated for books than for music: the music publisher does not need to seek permission from the artist's estate to convert old vinyls to new formats while book publishers have to; the relevant court decisions were different for books than for music. Differences in licensing and rights helps explains the difference between post-wall music and post-wall books; differences in costs of digitisation explains the difference between pre-wall music and pre-wall book availability.

Can we please have Congress stop extending the duration of copyright?

* Caveat: at page 13, Heald says that David Lee Roth's version of "Yankee Rose" is "what looks to be a heavy metal tune from the '80's." This is clearly wrong. Van Halen under Roth was hard rock. But Roth's later solo efforts, including Yankee Rose, were much closer to the hair rock offered by the likes of Poison and Warrant. It's almost a genre self-parody. To call it metal, well, the boffins at the New Zealand Ministry of Culture sure know better.

** While Smith et al's propensity score matching method looks very sound on a per-book basis, I doubt that their $740 million figure is right. The per-book likely sales figures are likely correct, were we only to have a few of these books digitised. But adding more than 2 million new books into the mix, well, I expect that a lot of them are reasonably close substitutes for each other and we'd pretty quickly hit attention constraints: the total sales for all of them would be rather less than the sum of sales for each one were each one released on its own.