I'll be in tomorrow's budget lock-up and on TVNZ's ridiculously early Breakfast panel pre-budget roundup ahead of it.

For rather some time I've been making the case that government needs to retrench Core Crown Expenditure to pre-Covid levels.

The Great Wellbeing Budget of 2019 was not austere. It was a substantial increase in spending, as a fraction of GDP, as compared to the prior National government's last budget.

So.

Take every Vote from Budget 2019 as a percent of GDP.

Make that the baseline for a future budget. Maybe 2025 if they're somewhat ambitious, 2026 if less ambitious.

Some programmes or structural changes since Budget 2019 might be considered worth keeping. Government would have to trim other spending so there'd be room for it.

I'm less interested in overs and unders around automatic stabilisers. Benefit spending will be higher in 2025 than 2019 because unemployment is likely to be higher; note too though that jobseeker numbers remained very high relative to unemployment over the period after lockdowns.

If Budget 2025 were "Hey, this is the same as Budget 2019 would have been, as a fraction of GDP, if unemployment had been at 2025 levels", all good. There would be no structural deficit.

Let's compare a few numbers here.

At Budget 2019, Treasury put up forecasts of Core Crown expenditure for the year to June 2023. The bulk of Covid spending should have been 2020 and 2021. The traffic light system ended in September 2022.

Budget 2019 forecast a 4.3% 2023 unemployment rate. The 2023 half-year fiscal update had a 3.6% unemployment rate for year to June 2023. So higher unemployment isn't responsible for any differences in spend between 2019's forecast 2023 and the actual 2023.

Let's compare Budget 2019's forecast for core crown expenses by functional classification for 2023 with actual expenditure by those classifications for the year ended June 2023, inflated by the extent to which nominal GDP for 2023 exceeded 2019's forecast GDP for 2023. Nominal GDP in 2023, divided by the forecast of 2023 GDP from Budget 2019, then multiplied by each functional classification line.

Overall, Core Crown spend is $13.4b higher than had been expected in 2019, after inflating for nominal GDP increase over the period, and accounting for Budget 2019's expectation of about $10 billion in new operating spending by 2023 that couldn't be classified in 2019.

Or put it this way. Budget 2019 expected Core Crown spending in 2023 would be about $104 billion across those functional areas, plus $10 billion in new operating spending, for $114b all up, after adjusting for nominal GDP growth to catch population increase and inflation.

Actual 2023 was almost $127 billion. So $13.4 billion more than would reasonably have been expected.

Despite unemployment being a lot lower in 2023 than had been forecast in 2019 for 2023, social security and welfare spending were $3.8 billion higher than had been forecast for 2023 at Budget 2019.

Health spending was $7.7 billion higher.

Finance costs are substantially up, and there won't be much government can do about that now other than avoiding making things worse.

Transport is $1.8b higher. Core government services $1.6b higher. Education $1.5b higher.

Spending has blown out across the board. If you take the excess spend as a proportion of the had-been-forecast spend, the blowout is of course biggest in finance costs, with with housing and community development (60.3%), heritage, culture and recreation (57.8%), environmental protection (52.2%), primary services (48.9%), and transport and communications (47.1%) following - health only blew out by 36.8% as compared to forecast and social security and welfare by only 9.9%. But those two line items are so very very big.

Getting back to Core Crown expenditure comparable to 2019's when measured against current GDP isn't a small job.

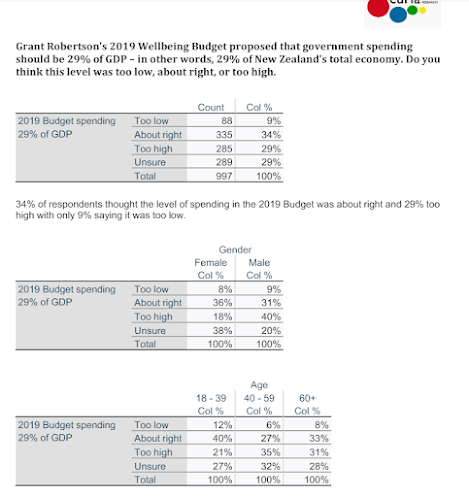

The Taxpayers Union commissioned a poll from Curia. Sample of 1000 respondents.

They wanted to know whether people viewed Robertson's Wellbeing Budget, with Core Crown spending of 29% of GDP, as being too low, about right, or too high.

Only Green Party supporters reported that it was too low, or at least in any substantial numbers. Among Green supporters expressing an opinion, about half of Green supporters thought it was too low, and half thought it was about right.

Among the population at large, 9% thought it was too low, 34% about right, 29% too high, and 29% were unsure.

Among those expressing an opinion, those thinking spending in 2019 was too high outnumbered those saying it was too low by more than 3 to 1, with most saying it was about right.

It isn't crazy to view the pre-Covid spending proportions as a decent baseline. And most people didn't think Budget 2019 was austerity - far more people said that it spent too much, as a fraction of GDP.

Budget 2019 reckoned on Core Crown spend of 28.8% of GDP over the medium term.

December's Half-Year fiscal update had 2023 Core Crown spend at 32.2% - the mess I pointed to above. And forecast it would be worse for 2024 at 33.4% of GDP.

People rightly recognise Budget 2019 as not being austere.

Getting back to spending consistent with government's share of the economy in 2019 is still going to be a big job.

I'm hoping tomorrow to see reasonable work in that direction at least. Especially if they also want to deliver tax reductions, given the size of the deficit.

National will be damned as austerity merchants for any spending reductions, regardless of how many people viewed 2019's budget as too generous.

If you're going to be hanged anyway, better to be hanged for a sheep than for a lamb. I don't expect any sheep here. But they could at least aim for hogget.