Chile increased its sales tax on soft drinks above a threshold by 5%, from 13% to 18% (the high-tax soft drinks), and reduced its tax on lower sugar soft drinks by 3%; there's a separate no-tax soft drink category presumably covering diet drinks.The empirical evidence on SSB taxes keeps coming- more than for any other obesity prevention strategy @HelenClarkNZ @EricCrampton https://t.co/DBbdFpd3xK— Boyd Swinburn (@BoydSwinburn) July 4, 2018

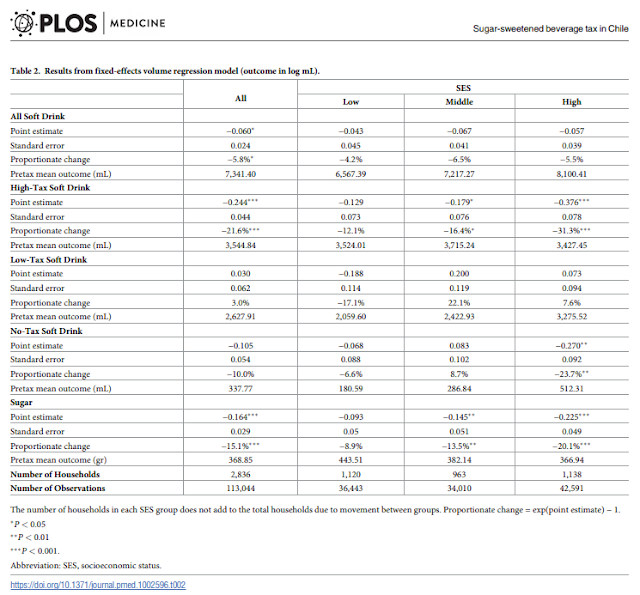

Here's the key table.

If we believe the result, increasing the tax on high-tax soft drinks by 5%, reducing it on low-tax soft drinks by 3%, and not changing the tax on no-tax soft drinks did nothing to consumption among low-SES groups but massively cut consumption of high-tax and no-tax soft drinks by high SES groups.

And the later tables say that tax pass-through was imperfect: there was a 1.6% increase in the price of all soft drinks: a 1.9% increase in high-tax item prices and a 1.7% drop in the price of low-tax items. So the wedge between high- and low-tax products, as seen by consumers, increased by 3.6%. The proportionate change in high SES consumption of high-tax drinks was a 31.3% reduction. Where we struggle to find evidence of effects in other studies, this one says there's an incredibly high price elasticity of demand among rich people but no effect among poor people.

Chris Snowdon finds the results unbelievable; I'm not sure he's wrong. The big drop in consumption of no-tax soft drinks suggests something else is going on.

Just as a guess - was the tax accompanied by a vilification campaign against soda generally? High-SES groups might then have responded but low-SES groups ignored the messaging. Low tax soda became cheaper, so there was some substitution to that category from both no-tax and high-tax soda that coincided with an across-the-board drop in soda consumption among high-SES groups. That is just a guess though. The results don't make a lot of sense.

In related news, commenter Nick R suggests the following:

Here's the thing about this debate. As far as I can see there is virtually no downside to the tax. Products that include a lot of sugar would cost more. So what? There is literally no hardship to that because nobody needs them. We can choose to buy them, or not. No biggie, and if we do buy them, the state gets the benefit of the revenue. So even if it has no effect on obesity at all it seems benign because the tax is largely optional, unlike (say) petrol duty. And if it does have an effect on obesity, even better.I always struggle when trying to see the world as people like Nick R see it. As I look at the world, if someone enjoys something, and you take it away from them, that has to be a harm to them as they see it. Like if Nick R enjoyed, I dunno, fancy cars, and I proposed a big luxury tax on the kinds of cars that lawyers like, surely it would sound ridiculous to claim "there is literally no hardship to that because nobody needs an Audi. Lawyers can choose to buy them, or not. No biggie, and if they do buy them, the state gets the benefit of the revenue." But it's nonsense, right? Those who buy something else instead are harmed by the tax. That excess of cost to consumers over the tax revenue to the state matters. And who am I to say that Audi-lovers should be taxed more than people like me who drive a ten-year-old Honda?

As Elron McKenzie might put it, "If everyone taxed all that they hated, where would we be? There would be nothing left. Because sooner or later, no matter how nice the things are that you like, somebody will hate those things too, and will want to tax them. And then, next thing you know, your favourite stuff is gone. So, like, what good is it, eh? So just keep the neutral GST."

I agree with your general argument, but I think your analogy is wrong. A more appropriate example might be a tax on diesel cars and a subsidy on electric cars.

ReplyDelete