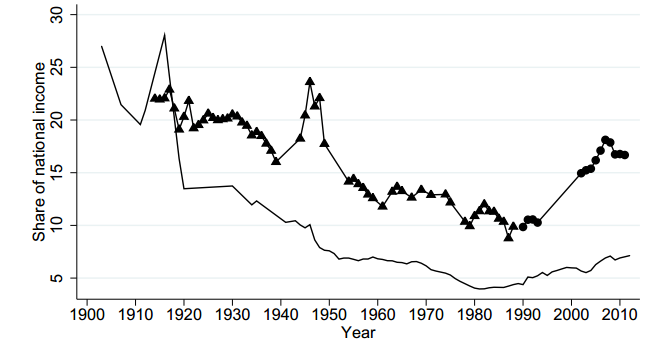

In both countries, inequality fell from the early part of the 20th Century through until about the 1980s. From 1990, inequality started increasing in both, with a much sharper increase in the country with the higher line.

Draw some conclusions about the policies in the country represented in the upper line. Would you say that:

- The graph clearly shows that policy went wrong starting around 1994, allowing the rich to exploit the poor.

- We cannot really tell whether the graph demonstrates generalised good things or bad things; we need to know why the shares changed before assessing anything.

- The graph clearly shows that policy improvements in 1994 stopped the wage compression that was hurting economic growth; we should expect that overall outcomes have improved since then as well.

I, likely obviously, go for answer #2. Rising or falling income shares for the top 1% tell us nothing on their own. If it's a Wilt Chamberlain process, I'm cool with that, though Chamberlain isn't everything. If it's instead some crony deal where we tax everybody a dollar and give it all to one person, I'm not cool with that, unless the money goes to me.*

Now that everyone's had enough time to draw their conclusions, we can reveal that the top line belongs to South Africa. The end of apartheid brought a sharp increase in the income share of the top 1%, as pointed out in a new NBER working paper from Acemoglu and Robinson. The bottom line is Sweden.

Their abstract:

Thomas Piketty's (2014) book, Capital in the 21st Century, follows in the tradition of the great classical economists, like Marx and Ricardo, in formulating general laws of capitalism to diagnose and predict the dynamics of inequality. We argue that general economic laws are unhelpful as a guide to understand the past or predict the future, because they ignore the central role of political and economic institutions, as well as the endogenous evolution of technology, in shaping the distribution of resources in society. We use regression evidence to show that the main economic force emphasized in Piketty's book, the gap between the interest rate and the growth rate, does not appear to explain historical patterns of inequality (especially, the share of income accruing to the upper tail of the distribution). We then use the histories of inequality of South Africa and Sweden to illustrate that inequality dynamics cannot be understood without embedding economic factors in the context of economic and political institutions, and also that the focus on the share of top incomes can give a misleading characterization of the true nature of inequality.On South Africa, they note:

No clear consensus has yet emerged on the causes of the post-apartheid increase in inequality, but one reason is related to the fact that after the end of apartheid, the artificially compressed income distribution of blacks started widening as some portion of the population started to benefit from new business opportunities, education, and aggressive affirmative action programs (Leibbrandt, Woolard, Finn, and Argent, 2010). Whatever the details of these explanations, it is hard to see the post-1994 rise in the top 1 percent share as representing the demise of a previously egalitarian South Africa.

And, across the OECD, skill-based technological change and increases in the size of the top firms explains much of the increase in earnings at the top. They caution that if a rising income share of the top 1% turns into entrenched political power, that can be disastrous; appropriate policy then should focus on institutional checks against power-grabs rather than wealth taxes.

* Gordon Tullock liked to give this example. The Tullock Tax would impose a small cost on each American but make Tullock about $300,000,000 richer. Despite that Tullock had a concentrated interest in such a tax, the tax never passed: the Logic of Collective Action isn't everything.